As a literacy educator, you may be familiar with your students’ typical reading responses. You might have assigned them a writing task of different types such as book reports, book reviews, or reading journals in order to check their understanding of books they read. Traditionally, these reading responses have been written on a paper, sometimes accompanying drawings. As digital technologies have developed, however, alternative reading responses using digital tools have been drawing more attention from classroom teachers and researchers, including digital multimodal reading responses (DMRR).

Why DMRR?

DMRR is a very engaging and creative task for K-12 students as reported in Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education (CITE Journal). Like traditional written reading responses, many researchers have found DMRR enables students to comprehend main ideas of the book, to express their aesthetic stances toward literature, and to evaluate information encountered in a book. In addition, DMRR facilitates students who struggle with written reading responses to actively engage in reading responses by using a wider range of modes afforded by digital tools such as written and oral language, static or moving images, and music and audio representations, as Hsiao-Chien Lee reported in Literacy Research and Instruction. In other words, DMRR and other multimodal compositions provide students with more diverse and engaging composition opportunities that help to broaden their semiotic toolkits, as found by Marjorie Siegel. Furthermore, teachers and students who participated in qualitative empirical studies reported that DMRR have improved not only students’ literacy skills but also their self-efficacies as learners. Therefore, using DMRR as one of your in-school writing or composing tasks can be beneficial to students.

Useful Digital Tools for DMRR

The availability of digital technologies may vary by schools across the United States. Some schools may have laptops or iPad carts for students in several classrooms whereas others may have only one or two computer labs for the entire school. To work with this varied availability of digital devices, I will introduce several digital tools for DMRR.

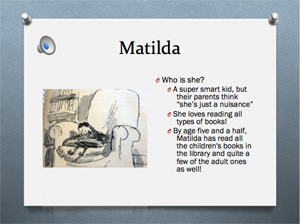

If you use a desktop or laptop: For younger kids in an elementary school, you can teach them how to design Microsoft Power Point slides with written language and simple images and then let them create their own reading responses. To help students use images aligned with their written language or other modes, you can take pictures of the book’s illustrations or students’ drawings and import them onto the slides. Students can also embed their voices or other sounds onto each slide by clicking “Insert,” “Audio,” and “Audio From File” or “Record Audio.” An audio-embedded slide includes the speaker icon and the slideshow plays the embedded audio automatically. The image included here shows one example of a slide that includes a captured illustration from the book Matilda and recorded sound about the slide. As your students become more skillful composers of DMRR with Power Point, you might then let them upload their slides to VoiceThread and engage them in providing multimodal feedback on a classmate’s book review.

If your students are older or more tech-savvy, I recommend you explore the opportunities provided in a free digital video-making program such as Microsoft’s Photo Story or Apple’s iMovie. These are free and default programs on Windows or OX system computers unlike other fee-based online video making tools such as Animoto and GoAnimate. These video-making programs have more advanced functions to customize narration, transitions of scenes, zooms, pans, and sound effects and music. These programs also have multiple options to share video products with others.

If you use a smartphone or tablet: Mobile educational applications are essential to create DMRR using smartphones or tablets. Many Web 2.0 tools have apps for computers, tablets, and iPhones. In my opinion, apps for tablets have simpler functions but can be ideal tools for students because these devices can be manipulated easily by touching their screen with fingers. For example, Apple’s iMovie can work on an Apple computer, iPhone and iPad. However, dragging and dropping images, recording voices and editing all modes in a video are much easier on iMovie app of the iPad than the same app of the Macbook.

ShowMe can be another useful tool to compose DMRR. This is a free interactive whiteboard app with which students can insert images, record voices, and draw shapes with different colors by fingers. If you want to keep your students’ products from non-classroom audiences, ShowMe is not a good option because it requires users to create an online account and share their final products on the “Learn” webpage before sharing through other Web 2.0 tools.

The more you know about the types of digital tools available to you, the better you can incorporate DMRR into your classroom instruction.

More digital tools you can explore:

Sohee Park is a doctoral student specializing in Literacy Education in the School of Education at the University of Delaware, sohee@udel.edu.

Sohee Park is a doctoral student specializing in Literacy Education in the School of Education at the University of Delaware, sohee@udel.edu.

This article is part of a series from the International Reading Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).