“When my teacher posts her videos, I feel like she is at home helping me learn whenever I need her.” —One of my fifth graders

Envision a classroom where students come to class filled with knowledge and excitement about a topic you are studying and ready to begin working on engaging activities as soon as they enter the room. “Flipping” your classroom can help you achieve this goal.

Envision a classroom where students come to class filled with knowledge and excitement about a topic you are studying and ready to begin working on engaging activities as soon as they enter the room. “Flipping” your classroom can help you achieve this goal.

Flipping is the concept of using teacher-created videos to deliver instruction prior to students coming to class, so class time can be spent working on projects and assignments that you would normally give for homework. By creating your own short videos (approximately one minute per grade level) for homework assignments, students build background knowledge. When they come to class, they can make stronger connections to the content, ask questions, and get to work on the enrichment activities. You become available to differentiate your instruction for the needs of each student. It’s a win–win: Everyone gets assistance at the level of instruction they need, and you get to teach the good stuff in class!

When I bring up flipping in my teacher education classes, students are usually intrigued as well as cautious and skeptical of the idea, which is a good thing. However, after three years of teaching preservice teachers, I have yet to find a student who doesn’t see the value of flipping the classroom. We start our investigation by learning about the SAMR Model of technology and studying the benefits of videos available through Khan Academy. We also research work of flipping pioneers, Jon Bergmann and Aaron Sams. If interested, you can connect with them and over 14,000 flipping practitioners on the Flipped Learning Network.

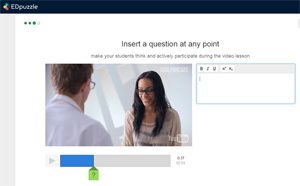

We explore applications like SMART Notebook Software, Screencast-O-Matic, and EDpuzzle. I like EDpuzzle because you can upload your videos and then add questions and stopping points to assist with processing and accountability of the lesson. It also lets you know who watched the videos and how students answer your embedded questions. We practice recording videos and then design lessons for 3–5 minute flipping videos that introduce a skill or strategy while holding students accountable for the content within the video.

Graphic organizers, entrance tickets, notes, answering questions, and other strategies are incorporated into the video presentations. We create lessons, practice them, and then record them on our Weebly teacher websites. When filming, we consider things like backgrounds, lighting, sound and voice quality, and that they don’t need to be perfect. By the end of the project, students are excited to be their own “Academy”—one where students and their families hear their messages and bond through the learning experience. One of my favorite benefits is that students can watch, stop, and replay the videos as many times as they want while learning content in addition to studying for quizzes, tests, and exams. How often do students have time to rewind you in the traditional classroom?

So where do you start flipping? I suggest the work of Bergmann and Sams. They know their stuff, are passionate about flipping, and understand the practical application as teachers themselves. Bergman was recently a guest blogger for Blackboard with a post titled, “What Academic Leaders Should Know About Flipped Learning.” Their website, FlippedClass.com, contains an amazing collection of introductory flipping videos sponsored by Edutopia’s Flipped Learning Tool Kit (or on YouTube). You can also access research, flipping tools, and contact information for questions on their website.

One very important message they share and I agree with is to make your own videos. This helps you bond with your students, engages them in the content you are teaching, and proves that you are still their teacher! Give it a try. I think you will enjoy the experience and the many benefits that come from flipping your classroom.

Mary Beth Scumaci is a clinical associate professor with the Division of Education at Medaille College in Buffalo, NY, and a mom of kids who flip. She instructs teachers in training and educators about integrating technology to enhance the curriculum while motivating and engaging learners.