From the schoolhouse bells to the rows of desks, educational systems were once constructed to mirror the centralized structure of industrial workplaces. However, postindustrial workplace structures are rapidly adapting to living networks of collaboration and creativity. How can educators design hybrid learning environments that prepare students for the deictic literacies of future workplaces?

From the schoolhouse bells to the rows of desks, educational systems were once constructed to mirror the centralized structure of industrial workplaces. However, postindustrial workplace structures are rapidly adapting to living networks of collaboration and creativity. How can educators design hybrid learning environments that prepare students for the deictic literacies of future workplaces?

Connectivism, as defined by George Siemens, is a learning theory that embraces the impact of a global society that adapts to rapidly changing Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) through real-time collaborative networks. When designing hybrid learning environments, the theory of connectivism provides an ecosystem for educators to move beyond hardcopy curriculum binders to an online living curriculum.

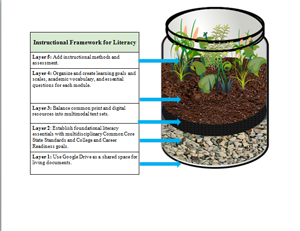

During the 2015–2016 school year, we worked with a rural school district in southeastern Pennsylvania as it began its second year of implementing Chromebooks within a hybrid model of literacy instruction. As defined by this school district, a hybrid model contains direct, collaborative, and independent learning using both print and digital texts. To help educators conceptualize connectivism, we use a terrarium as a metaphor to explain the process of cultivating a living curriculum.

Layer 1: Select a shared space for living documents

Just as the glass of a terrarium creates the environment for growing plants, Google Drive provides a space for educators to cultivate a living curriculum.Google Drive is a free, online file storage system that provides a space to create and collaborate with others in real time. Real time is an essential component of a living curriculum because it moves educators from individual planning to collaboratively designing hybrid learning environments. For example, teachers used the comment feature on Google Docs to post revision suggestions and questions as they differentiated their English language arts instruction.

Layer 2: Establish foundational essentials

Gravel, the foundational layer of a terrarium, is made of several different types of rocks. Like the gravel, educators need to determine the variety of essential skills students need to be successful in school and future workplace. For instance, Common Core State Standards and College and Career Readiness initiatives suggest learning goals by grade level and content area. Because literacy skills are required in every field of study, it was important for teachers to cultivate a living curriculum that provided opportunities for students to practice these multidisciplinary literacies.

Layer 3: Balance common print and digital resources

Charcoal filters out toxins in the terrarium so the plants can thrive. Layering in authentic and relevant texts, like the charcoal, cultivates an environment for students to thrive as readers and writers. Instead of buying new texts, teachers critically examined current resources (i.e., anthologies, basals, science and social studies textbooks) that were already predominate in every classroom. Outdated stories and articles were filtered out and replaced with free, online resources that support students’ diverse interests and reading levels. For instance, teachers were able to access free, digital archives of magazines like National Geographic Explorer, Highlights, and NewsELA. Even graphic novelists such as Andy Runton (Owly) offer free digital copies of their work. Teachers also integrated interactive digital videos (e.g., Wonderopolis, Playposit, and TED-Ed) to engage students and extend their background knowledge. The hyperlink feature in Google Docs enabled teachers to quickly link and access new resources to the living curriculum, which grew into relevant multimodal text sets that balanced authentic print and digital texts.

Layer 4: Organize and create module components

Adding soil to the terrarium provides a mix of nutrients crucial for plant growth. A module, like soil, contains a mix of eligible content crucial for effective literacy instruction. Using the Google Docs, teachers outlined four modules, one for each marking period, and sorted standards and resources in a way that allowed for a progression of learning. Though all domains (i.e., foundational skills, comprehension and vocabulary, writing and language, speaking and listening) were covered, careful thought was given to the amount of time students would need to master different skills. The organized list of multidisciplinary skills and resources helped teachers recognize patterns and connections to real-world situations. For example, teachers use to teach isolated units on story structure in reading, weather in science, and Post-Revolutionary War events in social studies. Analyzing organized eligible content across the module cultivated an environment that enabled teachers to connect these isolated units into one central theme that addressed the importance of understanding how changes in the world impact the way people relate to each other. As a result, Changes became the title of the first module. The last task in this layer required teachers to create 8–10 learning goals and scales, identify academic vocabulary, and pose essential questions as a way to clarify the behaviors and language students need to become inquiring, critical thinking citizens.

Layer 5: Add instructional methods and assessment

Selecting plants for a terrarium requires careful consideration of light, size of the foliage, and level of humidity. Because Google Docs have unlimited content capacity, teachers were able to carefully design a vibrant array of instructional methods and assessment. Each module contained seven cycles with six days of 90-minute English language arts instruction time. Within a hybrid learning environment, cycles were written to balance whole group, direct (small group), collaborative, and independent learning. Summative assessments were embedded at the beginning and end of each module to guide differentiating instruction. At the same time, formative assessments were embedded throughout each cycle to inform the level of scaffolding students required. Learning goals were paired with instructional methods to keep the learning fresh and vibrant. Teachers across the district, from three schools, were able to access the living curriculum, on demand, to add comments where instruction needed adjusted or to add links to new resources they created or found online.

Tending to a hybrid learning environment

The benefits of using Google Docs go beyond having teachers engage in ICTs in order to access the curriculum. Using Google Docs has cultivated a community of collaboration and connectivism, a sense that everyone is working as a team to tending to the living curriculum. Where scripted lessons were once provided in basal teacher manuals, educators now care for these living documents the same way they would a terrarium. Teachers continue to cultivate the hybrid learning environments by adding new or updated resources anytime from their devices with Internet access to Google Apps. Designated grade-level leaders review comments made on documents and make real-time changes that grow and adapt to the ever-changing technology, resources, and needs of students. In this manner, educators are able to keep the curriculum writing process in constant momentum without revisiting dead documents every five years. As a result, educators are invested in keeping teaching and learning alive.

Additional resources:

- A module for second grade.

- A cycle for second grade.

- A previous blog post about the three-week instructional framework we used to support teachers’ pedagogical technological and content knowledge.

Julie B. Wise is a doctoral candidate at the University of Delaware. You can follow her onTwitter. Meg Rishel is an Instructional ELA Coach for Eastern York School District. You can follow her on Twitter.

Julie B. Wise is a doctoral candidate at the University of Delaware. You can follow her onTwitter. Meg Rishel is an Instructional ELA Coach for Eastern York School District. You can follow her on Twitter.

This article is part of a series from the Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).