Over the last decade, schools have been increasing their technology infrastructure for a wide variety of reasons, including making school more engaging for students. Thus far, the benefits in regards to engagement have yet to materialize. In January, the Gallup Poll released its annual Student Poll results, showing that only 50% of students met the engaged criteria (involvement in and enthusiasm for school) and 21% of students were fully disengaged. According to the survey, engagement declines in every grade, beginning from 5th to 6th grade before bottoming out in 11th grade. Almost half (45%) of responses were neutral or disagreed with the statement “At this school, I get to do what I do best every day.” From 2012, engagement levels at each grade are down across the board, and active disengagement has risen in that time from 16% to 21% of respondents. Although technology may be part of addressing the engagement issue, our current uses don’t appear to be moving the needle. In turn, we might be better served by shifting our focus to engagement itself.

Over the last decade, schools have been increasing their technology infrastructure for a wide variety of reasons, including making school more engaging for students. Thus far, the benefits in regards to engagement have yet to materialize. In January, the Gallup Poll released its annual Student Poll results, showing that only 50% of students met the engaged criteria (involvement in and enthusiasm for school) and 21% of students were fully disengaged. According to the survey, engagement declines in every grade, beginning from 5th to 6th grade before bottoming out in 11th grade. Almost half (45%) of responses were neutral or disagreed with the statement “At this school, I get to do what I do best every day.” From 2012, engagement levels at each grade are down across the board, and active disengagement has risen in that time from 16% to 21% of respondents. Although technology may be part of addressing the engagement issue, our current uses don’t appear to be moving the needle. In turn, we might be better served by shifting our focus to engagement itself.

What do we know about student engagement?

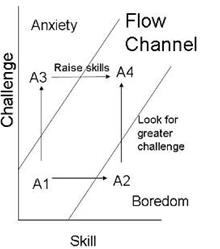

David Shernoff and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi have spent years studying engagement and how it is achieved. Full engagement—which Csikszentmihalyi has termed flow—is described as a fully immersive experience where all mental energy is going into a meaningful task. Our skills are matched with an appropriate challenge that stretches our ability, but not to the extent of frustration. Time seems to fly by, we feel in control, and in many cases forget about our outside troubles and shortcomings. Setting goals and using feedback to move toward those goals are also essential components. Larry Ferlazzo has a fantastic blog with additional resources on flow.

According to Shernoff and Csikszentmihalyi, student engagement exists when students experience high levels of three factors: concentration, interest, and enjoyment. Concentration is the focus and mental energy put toward a specific goal or task. Interest is conceptualized as a student’s level of intrinsic motivation to expend time and effort into a task or building specific skills. Finally, enjoyment is a student’s feeling of satisfaction as a result of participating in the learning event.

These conditions arise when students are presented with learning opportunities that they deem to be both challenging and relevant. Choice and control over the learning experience are crucial to student engagement. Mismatches between a task’s challenge and a student’s skill set can lead to anxiety or boredom. Additionally, student flow appears to be symbiotic with teacher flow as high student engagement leads to a teacher’s sense of flow as he or she builds his or her differentiation skills to meet the needs of students. Research suggests that traditional lectures, videos, and exams are typically some of the least effective means to increase student engagement. Well-structured, student-selected inquiry tasks, however, are an excellent method to help students reach “flow.”

Examples from the field

Previously, I’ve written about my own experiences coleading students in interest-driven inquiry via a structure known as Genius Hour. In these multiweek inquiry projects, students are given at least one class period per week to explore a topic of interest. Students then share their findings in a TED-style talk. We’ve made two changes to our model this year. First, we’ve used the Right Question Institute’s Question Formulation Technique to help students better articulate their inquiries via interesting questions. Second, we plan to link students with a mentor or “broker” who can help the student with their chosen project. There is a multitude of resources for implementing Genius Hour including websites, books, and a vibrant Twitter community.

Interest-driven digital inquiry can also be done effectively with specific content area constraints as well. History teachers at Attleboro High School in Massachusetts have been making inquiry a regular part of their teaching practice. In Nicole Lane’s Government Course, students spend the trimester investigating self-selected problems within the local community. Students explore the root causes and solutions via both Internet research and e-mails or one-to-one meetings with municipal and state officials and then publically present their findings at the end of the term. In another class, Ari Weinstein teamed up with science colleague Gregg Finale to create the cross-disciplinary course, Science and Public Policy. In this class, students have tackled topics such as how to install solar panels on school buildings and how to teach middle school students about global warning. An interesting wrinkle to this course is that students design their projects so they can be handed off to peers taking the class in the next semester, enabling future students to build on and expand the existing work.

Attleboro High School History department head Tobey Reed has been a strong advocate for the use of inquiry in history courses. “I believe that this is the way that people learn naturally so why would we try to get them to learn another way?” he asked. “I think that it engages them as well because they are invested in finding out the ‘answer’ or at least understanding the question.”

Making the pedagogical shift to inquiry, particularly digital inquiry, can be a challenge. “Almost all of it is foreign to them (students) because in many ways it’s the opposite of how they’ve traditionally done school,” said Attleboro history teacher Brian Hodges. “Students tend to struggle with asking good questions, finding and especially evaluating sources, contextualizing information they find and then turning it into a product.” Fortunately, teachers can now look to the Internet for resources to help improve students’ critical evaluation and digital authorship skills.

Despite the challenges, the benefits are extensive for students and teachers alike. Hodges explained, “Inquiry was difficult at the beginning because the idea was foreign to me, but the practice is way more engaging and way more enjoyable.” His students also appear to be reaching flow in these contexts. “There will be stretches in class when I’ll be going group to group and they’ll essentially tell me to go away and stop bothering them because they’re in the zone.” Reed said despite the extra planning, the digital inquiry project process makes it all worthwhile. “When the project is in full swing, it is way more fun to facilitate. The problems are unique and real. The questions are honest and the engagement is infectious.”

David Quinn is a doctoral student in URI/RIC PhD in Education program and a member of the Attleboro School Committee. Previously, he was a history teacher at King Philip Middle School in Norfolk, MA.

This article is part of a series from the Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).