In the book Words Onscreen, author Naomi Baron cites research that might surprise you: When it comes to reading for school, today’s students prefer reading on paper over reading onscreen. According to Baron, our students may compose copious amounts of digital writing on their personal devices, but when it comes to close reading, students still prefer printing a PDF and annotating it with a pencil in hand.

In the book Words Onscreen, author Naomi Baron cites research that might surprise you: When it comes to reading for school, today’s students prefer reading on paper over reading onscreen. According to Baron, our students may compose copious amounts of digital writing on their personal devices, but when it comes to close reading, students still prefer printing a PDF and annotating it with a pencil in hand.

Baron cites a study from late 2013 whose findings show that 84% of U.S. college students say they prefer print over digital text because it’s easier to bookmark and highlight. Baron readily admits this may change with time: “Annotation becomes easier on digital devices, especially for those who practice” (p. 30).

There’s no doubt that our students will get a lot more practice annotating online. In fact, annotating the Web is nothing new. The developers of Mosaic, one of the earliest browsers from the ’90s, envisioned a Web that anyone could annotate. And there’s no shortage of web annotation tools—AnnotateIt, Bounce, Diigo, Genius, and Marqueed, to name a few. But one tool I’ve been incorporating into my teaching lately is Hypothes.is.

Hypothes.is was developed using the standards of the W3C (the major governing body of the Internet), specifically the standards of the W3C Annotation Working Group. The mission of Hypothes.is is to enable a conversation over the world’s knowledge by creating an open platform for the annotation of any web document—images, videos, and data.

The easiest way to use Hypothes.is is to find a webpage you want to annotate and paste the URL into the search bar on the homepage of the Hypothes.is website. After that, a sidebar on the right of the screen appears allowing users to begin annotating. If anyone else has annotated the page, their public annotations are visible too. Another way to see what’s been annotated is to scroll through a webpage and then click on any highlighted areas.

You can add annotations by selecting an item on the page and clicking the annotate button; you then have a choice of making that comment public or private. Users have the ability to add tags as well. Some educators use tags to create streams of content based on a common term for the group. Then members can follow the group conversation more easily by following that tag. For example, one massive online open course on Shakespeare uses the tag moocspeare to help organize their conversations.

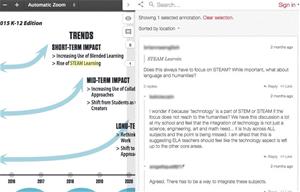

This past summer, I taught teachers getting their masters in educational technology. These educators came from three continents, and we viewed hypothes.is as a way to facilitate asynchronous discussions across multiple time zones. Pictured in this post is a snippet of our conversation about the NMC Horizon Report: K-12 Edition in Hypothes.is.

The interface allowed us to highlight the PDF of the text, make notes on it, and then reply to one another’s thoughts on the article. In addition, users can invite others into the conversation or share the annotations. A feature I find useful for my high school students is sorting annotations by date or by users, so that producing a portfolio of a student’s annotations for assessment is easy.

Baron is probably right that many of us still prefer annotating on paper when it comes to the close reading that we do for academics, but one of the affordances of web annotation is the potential for massively open online reading. Tools like Hypothes.is will make this only easier.

Chris Sloan teaches high school English and media at Judge Memorial Catholic High School in Salt Lake City, UT. In the summer, he is an instructor for the overseas cohort of Michigan State University's Master's in Educational Technology.