As a literacy teacher, I tend to look at the world in ways that others may not. I listen for figurative language in song lyrics, find the craft of argumentative writing on ESPN, and ask strangers reading The Hunger Games what their image of Cinna looked like after Lenny Kravitz was cast in the film. However, I learned more about literacy through the composition of one single writing task: my mother’s eulogy.

As a literacy teacher, I tend to look at the world in ways that others may not. I listen for figurative language in song lyrics, find the craft of argumentative writing on ESPN, and ask strangers reading The Hunger Games what their image of Cinna looked like after Lenny Kravitz was cast in the film. However, I learned more about literacy through the composition of one single writing task: my mother’s eulogy.

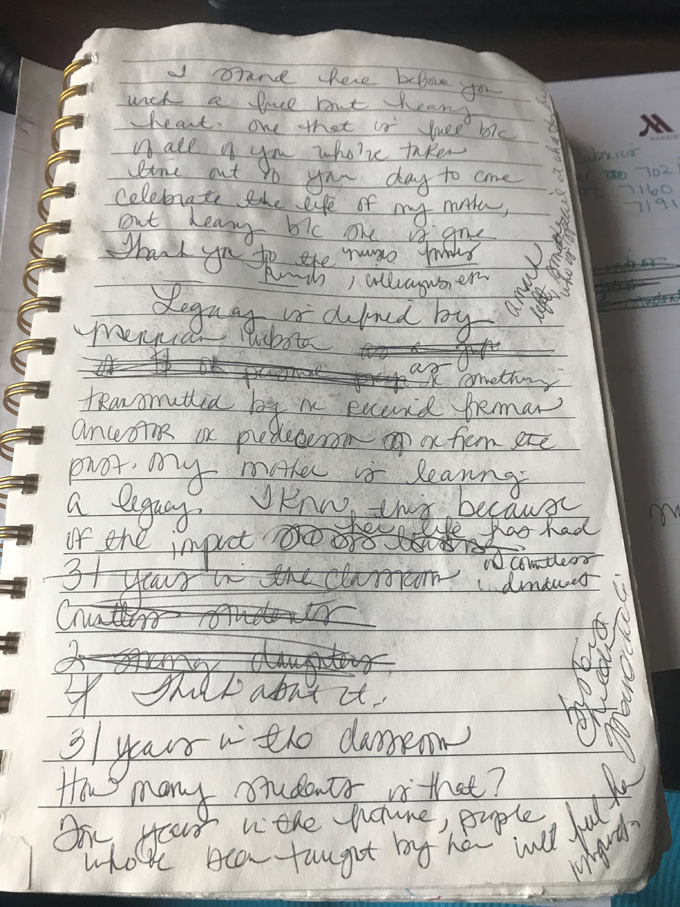

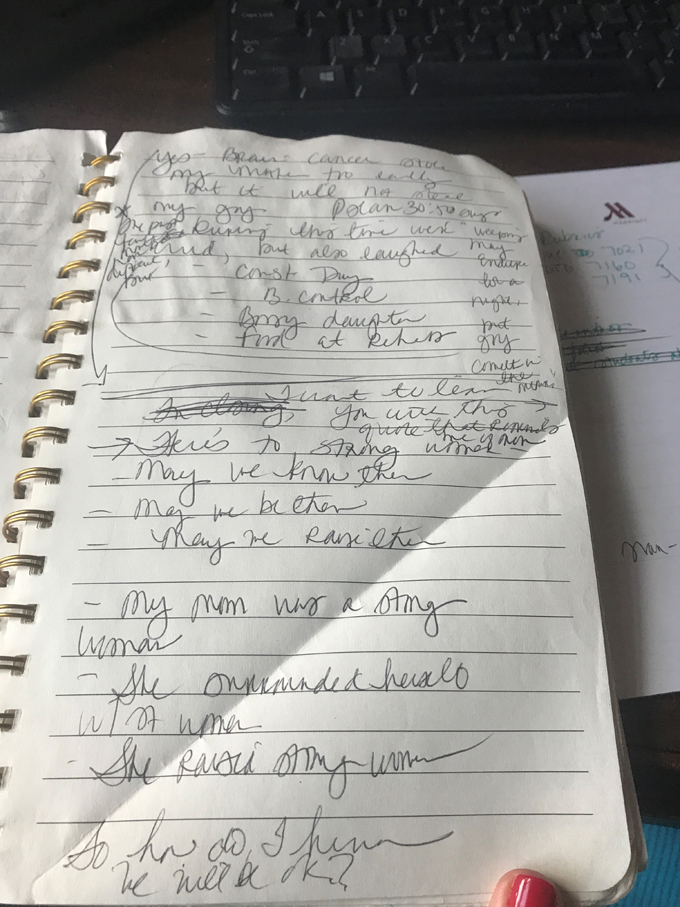

When my mother was diagnosed with inoperable brain cancer, I began the task of writing her eulogy. Not on paper, but in my head. For almost four months, I drafted this document in my head whenever I had time and ideas. In the hospital while she slept. On a plane to speak at a literacy conference in Arkansas. In a car line while waiting to pick up my children. At night when I could not sleep. However, it was not until the day after she died and the night before her funeral that I put pen to paper. The accompanying images are some of the documents I used as I delivered my mother’s eulogy at her funeral last December. If you notice, it looks messy. Haphazard. Unorganized. Yet these images represent almost four months of deliberate planning, drafting, and revision. Rewrites that existed only in my head, but which aided substantially in the final—yet not so final—product.

Drafting this piece made me seriously reconsider how writers plan, think, and revise. It also made me think hard about the emphasis that is often placed on written prewriting or planning. In fact, I am ashamed to admit that I required a graphic organizer for all writing tasks my first year of teaching. In many classrooms, my mental planning and thinking that went into the crafting of this piece would not have been acceptable. How can thinking be measured? How could a teacher assess my mental planning without some type of written piece of justification or evidence? These types of questions are often the very ones that prompt teachers to continue to use traditional teaching methods and assessments when it comes to writing instruction. However, any teacher could have assessed my thinking and planning just by simply having a conversation with me about my writing.

Drafting this piece made me seriously reconsider how writers plan, think, and revise. It also made me think hard about the emphasis that is often placed on written prewriting or planning. In fact, I am ashamed to admit that I required a graphic organizer for all writing tasks my first year of teaching. In many classrooms, my mental planning and thinking that went into the crafting of this piece would not have been acceptable. How can thinking be measured? How could a teacher assess my mental planning without some type of written piece of justification or evidence? These types of questions are often the very ones that prompt teachers to continue to use traditional teaching methods and assessments when it comes to writing instruction. However, any teacher could have assessed my thinking and planning just by simply having a conversation with me about my writing.

Here is what writing my mother’s eulogy taught me and reminded me about writing:

- Most writing is messy. Most of what we write in our daily lives never becomes published and polished. Instead, it functions mainly to inform, communicate, understand, explain, and process information. In the classroom, this tenet is especially important. For one, it gives students the freedom to write without the pressure of ensuring that every piece of writing they complete is publishable quality. In fact, 90% of what students should be writing in their classrooms should fit the previous descriptors. But here’s the really important part: Students should be writing in class every single day. Practicing writing for a variety of purposes gives students opportunities to improve basic skills and prepares them for writing tasks that need to be more polished and presentable. In my experience, many students care only about the letter grade and either ignore the comments if the grade is satisfactory or shut down completely if the grade is poor. With less emphasis on the final product, teachers should spend less time grading; qualitative, focused feedback may yield better results.

- Prewriting does not have to be written. One mistake I made as a writing teacher was requiring students to submit a graphic organizer or other form of written prewriting as proof that they had planned their writing piece. Although the written prewriting task did aid some students in the construction of their composition, I found that others haphazardly filled in the obligatory organizer at the end of the writing task so they would not lose points for omitting this portion of the assignment. This is not the true purpose of prewriting, planning, or both. Some tasks require more planning than others. Planning and prewriting need not be written; valuable planning may take place through thinking or oral discussion. These venues are no less important than written ones.

- Revision is ongoing. Revision is not a destination; writers do not simply arrive at the revision step, complete the task, and move on to the final draft. Rather, revision and writing are recursive processes that are ongoing and certainly not linear. While I was drafting Mom’s eulogy in my head, I was also revising and modifying the writing, whether it was in phrasing, word choice, or organizational structure. Revision is a sophisticated process and is not as simple as capitalizing letters and adding punctuation (that’s editing). Revision requires writers to revisit their pieces, consider their audience, think about the words they chose, and make decisions about the flow, purpose, and voice of their piece.

When designing and implementing writing engagements in the classroom, I implore teachers to consider these principles. Instead of focusing on a final product or the steps within the process, teachers can encourage and facilitate writers as they plan, revisit, and revise. Acknowledging these simple principles offers opportunities to nurture and support writers as they wade through a variety of writing engagements in both the academic and personal realm.

Rebecca Harper is an assistant professor of literacy at Augusta University. She received her PhD in Language and Literacy from the University of South Carolina. She is the author of Content-Area Writing that Rocks (and Works!).