In many classrooms I visit, students do not raise their hands. They are taught early on how to participate in discussions where raising hands isn’t necessary. They respect the speaker’s turn, they listen carefully, and wait for an opportunity to respond. The teacher acts as a facilitator or a coach for the conversation, not as the sole channel though which information can pass. In these conversations, questions are valued as highly as answers. The goal is to create new ideas, ideas that perhaps even teacher had not considered, not to regurgitate old ones.

Although it is so easy to default to the standard way of running a discussion, hands raised, teacher calling on one at a time (often the same few), there is magic when you say to students, “Put your hands down. I’m not going to call on anyone. Just speak when you have something to say.” Doing this sends the message that your students’ voices are just as valuable the teacher’s.

So what happens in a truly great great whole class discussion? A few ideas might come to mind:

- Students listen carefully to one another and respond directly to others’ comments.

- One or a few topics are explored in depth.

- New conclusions, understandings, and ideas are grown.

- New questions are raised.

- All students’ voices are heard.

Build students’ vision of strong talk

Lucille Clifton has said, “We cannot create what we can’t imagine.” Similarly, we cannot expect students to engage in strong discussions if they do not know what these look like. To find samples of strong classroom conversations, you might need look no farther than your school building. If you know a classroom where strong talk is taking place, take a few minutes of video to show to your students (make sure your school’s videotaping policies allow for internal use of students’ images, of course).

Or you can find videos online that show students engaging in discussions worthy of studying.

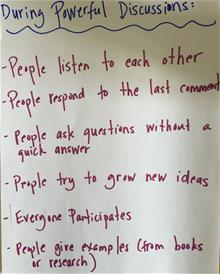

After watching the conversation, debrief and ask students to name some of what they noticed that helped the conversation to go well. Record these on a chart that will serve as a reminder for students when they are engaged in their own discussions. Because these ideas are student-generated, they will take on greater significance in your classroom.

After watching the conversation, debrief and ask students to name some of what they noticed that helped the conversation to go well. Record these on a chart that will serve as a reminder for students when they are engaged in their own discussions. Because these ideas are student-generated, they will take on greater significance in your classroom.

Guide students to assess and set goals to get better at discussion

Most students understand that they are working on building their skill sets in subject areas such as reading, writing, and math. Many students set goals for themselves in these areas, and, rightly or wrongly, judge their progress against that of their peers. They know, for example, that in math they are working on getting better at converting improper fractions to mixed numbers and that in reading, they are working on developing theories about characters. But many students don’t have a sense of their skill level when it comes to discussion, and some aren’t aware that building skill in discussion is not only possible but also vital.

Create a simple rubric or checklist with your students using the ideas they generated about good discussions to help them understand what they need to do in order to get better at accountable talk. Tell them they’ll have a chance to assess their own work during a discussion so that they can get a sense of what they’re doing well and what they need to work on. Then, lead the class in a discussion (recording this for future viewing can be useful).

After the discussion, you can ask students to assess themselves using the rubric or you can to fill out one rubric together, considering a discussion is something the entire class creates.

In addition to helping your students to assess their skill at discussion, you can also assess their stamina, the length of time they can keep a rich conversation going. It may well be that your students’ stamina for this kind of conversation is at about five minutes to start. If this is the case, keep in mind that marathon runners must train their way into running 26.2 miles. Record the length of time of the discussion as a benchmark, and encourage students to aim to sustain their conversations for longer and longer amounts of time as the year progresses.

Plan instruction to strengthen students’ talk

Here are a few teaching ideas that can help move your students’ discussions from so-so to great.

Here are a few teaching ideas that can help move your students’ discussions from so-so to great.

- Model effective discussion techniques. Before students are ready to take the discussion reins, they’ll need plenty of teacher modeling. For example, the single most effective way to encourage your students to listen to each other right from the start is to listen to them. One way to model that you are listening is to repeat parts of class conversations in a way that shows you are really trying to understand. “So what I hear you saying is….”

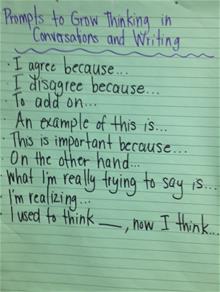

- Teach connective language. The Common Core Standards for Opinion and Informational Writing highlight the use of words and phrases to link ideas and information. Those familiar with the work of the Reading and Writing Project and with Harvey Daniels and Nancy Steineke’s Literature Circles will be familiar with thought prompts such as: For example… This is important because… On the other hand… and What I’m starting to realize is…to help students make connections between ideas in conversations. Making these prompts visible in a chart such as the one above and referring to them often will ensure that these phrases become an ingrained part of the way students talk, and eventually, the way that they think.

- Use visual supports to encourage inclusion. A major goal of discussion is to ensure that all voices are heard. A simple way to help students to understand the patterns in their language is to trace the conversation visually. To do this, create a chart by writing students’ names where they sit in discussions. Then, trace a line from name to name as students participate during a discussion. Analyze the discussions’ pattern and discuss how students might invite those whose voices were not heard to participate.

- Confer with students individually as needed. Some students might need some extra coaching to get better at classroom discussions, either one on one or in small groups. Use language from the rubric as much as possible in your instruction so that students are crystal clear on what they can do to improve.

- Build in frequent opportunities for students to self-evaluate. Be sure to revisit the rubric you created, perhaps even at the start and end of each discussion at first.

Anna Gratz Cockerille is an educator, writer, and consultant. In addition to her years teaching Upper Elementary in New York City, Anna has taught and coached in K–8 classrooms in Sydney, Australia; San Pedro Sula, Honduras; and Auckland, New Zealand. Anna has been a staff developer for the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project at Columbia University and presents at national conferences. Anna also conducts staff development in schools, helping teachers hone their balanced literacy practices.

Anna Gratz Cockerille is an educator, writer, and consultant. In addition to her years teaching Upper Elementary in New York City, Anna has taught and coached in K–8 classrooms in Sydney, Australia; San Pedro Sula, Honduras; and Auckland, New Zealand. Anna has been a staff developer for the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project at Columbia University and presents at national conferences. Anna also conducts staff development in schools, helping teachers hone their balanced literacy practices.