by Paul Morsink

Of all the instructional concepts in the experienced ELA teacher’s toolbox, one of the most important and practically useful is the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). Together with scaffolding and differentiated instruction, it provides the conceptual foundation for the experienced teacher’s daily labor of intellect and love—continually adjusting instruction and supports so as to maximize each individual student’s learning.

The key insight here is that it is essential to keep each student in his/her personal ZPD, tackling tasks whose level of difficulty is such that they are too hard to accomplish independently, but can be accomplished with support. Otherwise, if the work is too easy, students learn nothing new and become bored. At the other extreme, if the work is much too hard, they learn nothing and become frustrated.

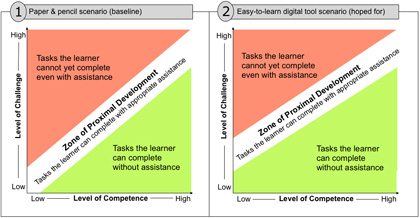

In this graphical representation of the Zone of Proximal Development, tasks in the white band (between the red and the green areas) are tasks a given learner can complete with appropriate assistance.

The experienced ELA teacher is thus continually performing an intricate balancing act—and doing it as many times and in as many ways as he/she has students with different learning levels and profiles. Each student’s ZPD is slightly different or very different from her classmates’. Also, the experienced teacher knows that scaffolding must be varied: particular types of scaffolding are more and less effective for different students.

For example, an experienced teacher knows that a little just-in-time verbal coaching works well for one student (let’s call him Shane). If Shane receives this coaching, he will succeed in creating an outline for the paragraph he’s about to write, and with an outline in hand, his writing is going to be much more coherent. (Someday soon, Shane will internalize this coaching and create an outline on his own.) In another case, Lauren’s teacher knows that reading with her partner Courtney is a powerful scaffold. Lauren pays close attention to the text and follows Courtney’s lead in asking probing questions about characters’ motivations. And so on down the line.

Which brings me (together with a group of K-12 teachers with whom I’ve had the pleasure of discussing these issues) to the question we’d like to pose to this blog’s readership: How has this ZPD-centered dynamic been affected by the digital revolution we’re currently living through? Specifically, what new steps or issues does a teacher need to consider when—inspired by reading a TILE-SIG article—he/she decides to bring a new digital tool into the classroom?

(We thought this blog would be a particularly appropriate place to raise this question—given that we’ve so often had this experience of reading here about a new literacy web tool and then rushing back to our classrooms with plans to have our students use it.)

To seed what we hope will be an ongoing conversation, we’ll share four brief observations.

1. Just as each of our students has his/her individual ZPD for reading complex texts or writing expository text, so we’re finding that each of our students has his/her own individual ZPD for learning how to use a new digital tool. What is challenging for one student may not be challenging for others, and the scaffolding that is helpful for one student may differ from what is helpful for others.

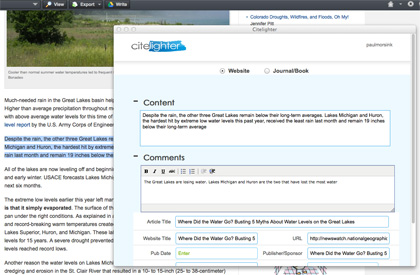

2. The upshot of (1) is that, as we think about introducing our students to a new digital tool, we find ourselves having to consider a greater number of ZPDs than ever before! As well, when we introduce a new digital tool not for its own sake, but rather to support and scaffold a larger reading or writing activity, we’re looking at a situation where one ZPD (for using a tool such as CiteLighter, for instance, to conduct and annotate research online) is in a sense superimposed on another ZPD (for taking notes from sources, for example).

3. In light of (1) and (2), we find ourselves becoming more and more expert at telling apart those digital tools that appear to match up well with our general needs and preferences, as well as with the varied types of scaffolding we expect to provide to get every student “up to speed”. For example, we become more skilled at not inadvertently disadvantaging some students who happen to take longer to learn how to use a new tool because of their starting level of expertise with computers and the available scaffolds within that tool.

4. Finally: it is important to note that we are not striving to develop our students’ expertise with digital tools for the sake of learning about the tools themselves and how they work (e.g., how it’s possible, technically, to apply yellow highlighting to a webpage). Rather our goal is to scaffold their understanding about such things as taking notes and the difference between summary and paraphrase. Thus, because of these ideas, we have coined a new term: the “Digitally Enhanced ZPD” or “DE-ZPD.” What we’re looking for in the digital tools we use in our classrooms is quick evidence that they will enhance our students’ existing ZPDs—for learning how to take notes, for example, or for writing research papers. That is, we seek to capture evidence that our students’ understanding of the curriculum is facilitated, deepened, and/or accelerated. We are less excited about the reality of having to deal with the multiplication of ZPDs (as described above) that will then require us to monitor and plan for these complexities with additional scaffolds and supports. This feeling is especially acute in the case of complexities that derive from the idiosyncratic design of a particular digital tool.

This "before" and "after" graphic depicts what teachers hope for when they introduce a new digital tool to support students' work on a particular activity to develop particular skills. The graphic depicts that, when this student started working with the tool (scenario #2), he was able to complete more tasks than before without other assistance. With appropriate assistance (and the digital tool), the student was able to complete a greater number of more challenging tasks.

Do these observations resonate to some extent with ones you are making in your classroom? We hope so. And we hope you will chime in and share your thoughts and observations—in comments to this blog and/or in conversations with colleagues in your building.

References

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Paul Morsink is a doctoral student in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology at Michigan State University, morsinkp@msu.edu.

Paul Morsink is a doctoral student in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology at Michigan State University, morsinkp@msu.edu.

TILE-SIG Feature: Curating and Sharing Your Toolbox of Digital Reading Supports with PLEs and PREs by Paul Morsink

TILE-SIG Feature: Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions of Digital Tools for Writing Instruction