Of all the books I’ve written, the one used most often as a springboard for classroom learning projects is The Lemonade War, the first in a series of middle-grade novels. In the book, Evan and Jessie get into a fight about who can sell the most lemonade in the five days before school begins. It’s a story of sibling rivalry, competition, and conflict resolution. And math. And business. After all, how could you write a story about competing lemonade stands without including math and business?

Indeed, the math/business angle is one of the things that sets the book apart, and one of the comments I hear most often from teachers is that they love the way math and business concepts are integrated into the story.

Well, the truth is, I never even thought about that “angle” when I was writing the book. I was just tapping into who I was as an elementary school kid: When I was a kid, I loved money. I loved earning it, counting it, saving it, (occasionally) spending it, and sometimes even giving it away. I started babysitting when I was ten and making crafty stuff that I could sell in the local consignment shop when I was twelve. By the time I was fourteen, I had a regular eight-hour-a-week paycheck job (at the local library, of course!). I was my own “business.” And business required math skills.

So when I wrote about Jessie’s love of graphs and Evan’s triumph in solving a math problem using pictures, I wasn’t doing it to provide a teaching moment in the book. It just felt true to the characters and the story I was telling.

But I will say here and now that I’m thrilled the book has found this dual purpose. The Lemonade War has been embraced as a One School, One Book offering, and so the classroom learning projects for the book often span grades K–6. Here are just a few of the ways in which smart, energizing teachers are using The Lemonade War to get their kids excited about math and business.

Gross Profit vs. Net Profit

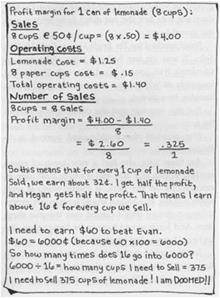

A fundamental business concept is the difference between gross profit and net profit. The money you take from your customers isn’t what you “earn,” because you have to subtract the cost of doing business. This is a concept that is reinforced throughout the book as both Evan and Jessie struggle to increase their profit margins.

A fundamental business concept is the difference between gross profit and net profit. The money you take from your customers isn’t what you “earn,” because you have to subtract the cost of doing business. This is a concept that is reinforced throughout the book as both Evan and Jessie struggle to increase their profit margins.

At first, all the lemonade supplies are “donated” by Mrs. Treski, and so gross profit equals net profit. But from that point on, the kids need to buy their own supplies (for example, lemonade mix and cups). It’s a sad moment when Jessie realizes in Chapter 8 that in order to win The Lemonade War, she would need to sell 375 cups of lemonade. “I am DOOMED!!” she writes.

Figuring gross profit, net profit, and profit margin involves addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, fractions, and percentages. Needless to say, kids are a lot more engaged in doing this math work when it involves their own lemonade war—and that’s what many schools do.

Rebecca Lynn Bowling used The Lemonade War when she was a fourth-grade teacher at Mullins School in Pikeville, Kentucky. “We decided to have a real-life Lemonade War,” explains Bowling, with classrooms competing against each other to see who could sell the most lemonade in one day. Each classroom wrote up a business plan for their lemonade stand, created advertising, and then came to school ready to sell. On the day of the war, the students assigned to work the lemonade stand “came dressed alike in matching attire. It was awesome!” In addition to calculations of profit margins, the project required the students to practice problem-solving, inferring, predicting, evaluating, and summarizing.

It’s also possible to launch a “virtual” Lemonade War, which is the approach taken by Mandy Marlo, a sixth-grade Language Arts and Social Studies teacher at Chagrin Falls Intermediate School in Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Marlo explains, “Our sixth-grade social studies classes used an interactive lemonade stand website to explore supply and demand.”

Each student started the month with three dollars and ran the virtual lemonade stand for 30 days. Every day, the website would give the student a weather report, that day’s cost-per-glass for making lemonade, and the opportunity to buy advertising. The student then entered how may glasses of lemonade he or she wanted to make that day, and the website would generate that day’s profit/loss. The students charted their results using the following organizer.

Marlo taught the students “trade and economics” vocabulary words and required the students to use these terms in a written reflection that asked questions like, “How did you know what you needed? How did you decide how much to spend? Were you satisfied with your results? How would you improve your lemonade stand?”

In addition, Marlo’s school helped create excitement for all aspects of the learning project by having a kick-off event that included an assembly for the whole school and a skit featuring teachers operating competing lemonade stands and vying for one particular customer by using business concepts described in the book.

Writing a Business Plan

The concept of “planning” has applications throughout life. In business, it’s particularly important.

Diane Smaracko, a fourth-grade teacher at Rye Elementary School in Rye, New Hampshire, connects the book with math and business skills when she teaches a unit on regions and their economies. “We make the connection to economics by reading different passages about businesses and profits.” Then she gets the kids thinking about how to plan a successful business by engaging in the following activities:

- Brainstorm a list of things you would need to have for a lemonade stand.

In Chapter 2, Evan and Scott Spencer gather all the things they need for a lemonade stand. - Design a lemonade sign.

In Chapter 3, Jessie and Megan design a sign to sell lemonade. - Think of two ways to add value to your lemonade stand.

In Chapter 6, Jessie and Megan figure out “value-added” strategies to boost sales. - Look up the word “franchise” in the dictionary and copy the definition.

In Chapter 8, Jessie and Megan launch thirteen franchises to maximize their earnings.

Likewise, Rebecca Bowling had her fourth-grade classes create business plans for their lemonade stands after reading the book. “Each classroom team had to come up with a business name, what kind of lemonade they wanted to sell, how much they wanted to sell, and how many containers of lemonade and cups to purchase. Students had to figure out how many cups would be used for one container of lemonade. They had to come up with a fair price for large cups and small cups. The also had to come up with ‘added value’ to their lemonade by offering cute straws, cookies, cupcakes, suckers ...”

In Estes Park, Colorado, the students at Estes Park Elementary School created class stores. Fifth-grade teacher Erin Leonhardt recalls, “We made a business plan. Students created displays (like the science fair tri-folds) that advertised and set a price point. They sold items like duct tape wallets, used books, and crafts. Students went shopping with ‘kid money’ that they earned in class.” An extra lesson in economics was added by an all-too-common classroom challenge: running out of time! “When we ran out of time, [the students] either dropped prices or raised them for supply and demand. I really think they got a lot out of it.”

Advertising

Perhaps the most common activity at all the schools was creating a poster to advertise a business or product. Marketing is an important plot element in The Lemonade War, with the characters creating signs for their businesses. Likewise, students in the schools had a lot of fun considering the principles of advertising and putting those principles to use.

As Diane Smaracko notes, “Great advertising keeps the products on the consumer’s mind.” She asks her students to think about how advertisers do this. Then the students design their own lemonade signs. “The children love designing their own lemonade stands and posters and figuring out ways to attract customers,” says Smaracko.

At Mullins School in Kentucky, Rebecca Bowling found the same enthusiasm for this activity. “The students designed posters advertising their lemonade stands and displayed them throughout the school. It was wonderful how they discussed the slogans they wanted to use on their posters!”

In Chagrin Falls, Mandy Marlo had her sixth-grade students create an advertisement for the lemonade stand that would benefit their sister school in Cleveland. She encouraged kids to “include anything that you think would help increase your business.” Kids responded by describing the lemonade, pointing out the affordability of the drink, using colorful and eye-catching graphics, and encouraging patrons to buy because the proceeds would benefit charity.

Charts and Graphs

In Chapter 8 of the book, Jessie realizes she might actually win the Lemonade War if she opens several franchises. The power of her plan becomes apparent when she creates a graph of potential earnings.

Mandy Marlo had her students chart data from the interactive lemonade stand website. Rebecca Bowling had her students create bar graphs to identify their favorite kinds of lemonade. Pie charts can be used to understand the relative costs of various supplies needed to run a lemonade stand. Line graphs and bar graphs work well to show profit and loss. In fact, the number of ways that charts and graphs can be used in the classroom to compare business practices is almost limitless.

The Final Connection

As Jacob Marley exclaimed in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, “Business! Mankind was my business!” And so it seems to be at each school that the question of what to do with money earned often leads the students back to this principle: “The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence were all my business.”

Students in schools across the country chose to give all or some of their profits to a variety of charities: a local animal shelter (as Jessie does in The Lemonade War), a sister school in need of books for their library, a local food bank. Many schools also donate their lemonade money to Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to helping fund research to end childhood cancer.

ALSF is an organization that I’ve worked with for several years. Each year, they run the Great Lemonade War Contest with the Grand Prize being a visit from Yours Truly to the winning school. It’s always wonderful to visit the schools and hear about how they used the book to learn about math and business and give back to the community.

Come see Jacqueline Davies co-present "Close Reading of Trade Books: Developing Thoughtful, Curious Readers Using Novels in the Elementary Classroom" with Carol Jago at IRA’s 59th Annual Conference, May 9-12, 2014, in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Jacqueline Davies is the talented author of both novels and picture books. She lives in Needham, Massachusetts, with her three children.