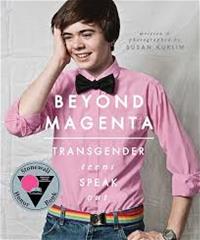

Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out. Susan Kuklin. 2014. Candlewick.

Ages 15+

Summary

In Beyond Magenta, a Stonewall Honor Book,Susan Kuklin offers a “spectrum” of transgender and gender-neutral teens as told through the words and photographic images of six individuals. Whereas the first five stories in the book share experiences of coming out as trans and relationships with family, friends, guardians, and teachers, the concluding chapter, the “lifeline,” tells the story of Luke, who found compassion and acceptance in his community through theater. Luke’s story begins with poetry, the outlet that gives him the security and space to explore his identity outside of society’s constructs.

In Beyond Magenta, a Stonewall Honor Book,Susan Kuklin offers a “spectrum” of transgender and gender-neutral teens as told through the words and photographic images of six individuals. Whereas the first five stories in the book share experiences of coming out as trans and relationships with family, friends, guardians, and teachers, the concluding chapter, the “lifeline,” tells the story of Luke, who found compassion and acceptance in his community through theater. Luke’s story begins with poetry, the outlet that gives him the security and space to explore his identity outside of society’s constructs.

The first five chapters of the book articulate the individual stories of five teenagers and young adults and explain what it means to be trans; these stories depict case studies of experiences couched in sometimes brutal reality. Through interviews dispersed with her own comments, Kuklin carefully depicts each young person with authenticity, respect, and care. Beyond Magenta offers the reader, whether familiar with LGBTQ issues, a thought-provoking source to gain understanding of what it means to be transgender and provides special attention to appropriate pronoun usage, gender identification, and the process of transitioning.

Teachers will want to vet each chapter carefully and consider their students and their community. Some chapters are more graphic than others, but the subject is too important to ignore. For a complete discussion of the topic and education, see the chapter “‘Trans’ Young Adult Literature for Secondary English Classrooms: Authors Speak Out,” in sj miller’s forthcoming Teaching, Affirming, and Recognizing Trans and Gender Creative Youth: A Queer Literacy Framework (Palgrave Macmillan).

Cross-Curricular Connections

English, health, art, social studies, science

Discussion Topics

Identity

How important is gender to your identity? Does your gender inform your actions or do you act independently from your gender identity? Consider how you have been treated since you were a child. What activities interested you? What were your toys? How do you judge how boys and girls act? Briefly reflect on gender. How do you understand your gender identity? How do others expect you to act because of your gender? Imagine a world in which one element of your identity was changed (can be gender, race, socioeconomic status)—what would be different? How would you be different? How would others regard you?

Words and Images

How do the photographs (or lack thereof) inform the writing on each individual? What do the images add to or take away from the teens’ stories? How would this book be different without visual representations? What happens to you as a reader when you cannot visualize one teen?

Ideas for Classroom Use

Photo Essay

Prewrite: If you were to put a photo essay together to express your identity, what would it look like? What artistic license would you take? What would you include or not include to represent yourself visually? Does the representation change depending on your intended audience?

- Storyboard your photo essay: Decide what is most important to your essay in illustrating your identity.

- Create photo essay: Facebook album, tumblr page, photo album

- After compiling the essay, reflect on the outcome: Did it meet your expectations, do you feel that it accurately represents you, what would you add/delete/change? What limitations of the photo essay did you experience? Did you learn anything about yourself, your identity, the manner in which you express your identity through this project? Discuss the public or private availability of your essay. Were you surprised by the end result? What did you find challenging while working on the essay?

Interview a Partner

Have students compose a list of 10 questions they would like to ask a peer in regarding his or her identity. These questions should be general and applicable to anyone. Pair students and have each conduct an interview with his or her partner. Take field notes to include exact quotes and body language. Each student will then create a short visual essay of his or her partner based on the interview. A good place to start might be in childhood, moving forward to the present time. Use Kuklin’s style as a model for good interviewing techniques.

Diversity Challenge

Assign a diverse aspect to each member of the class. Use index cards with identifying personas: homeless teen living in his car, boy who likes girls only as friends, Latina who just arrived from Mexico, identified lesbian, mother of a trans teen, and so forth. Writing from this point of view might be safer; guide discussion carefully to disavow stereotypes.

Additional Scholarly Resources

Kuklin’s website includes interviews, articles, and reviews for Beyond Magenta.

Clemmons, K.R., Hayn, J.A., & Olvey, H. (in press). “Trans” young adult literature for

secondary English classrooms: Authors speak out. In sj miller (Ed.), Teaching, Affirming, and Recognizing Trans and Gender Creative Youth: A Queer Literacy Framework. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mason, K. (2008). Creating a Space for YAL with LGBT Content in Our Personal Reading: Creating a Place for LGBT Students in Our Classrooms. The ALAN Review, 35(3). Retrieved from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ALAN/v35n3/mason.html

Additional Literary Resources

Andrews, A. (2014). Some assembly required: The not-so-secret life of a transgender teen. Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers.

Hill, K.R. (2014). Rethinking normal: A memoir in transition. Simon & Schuster Books for Young People.

Katcher, B. (2009). Almost perfect. Delacorte Books for Young Readers.

Peters, J.A. (2006). Luna. Little, Brown and Company.

Wittlinger, E. (2011). Parrotfish. Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers.

Judith A. Hayn is professor of Secondary Education at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. She is a member and past chair of SIGNAL, the Special Interest Group Network on Adolescent Literature of ILA, which focuses on using young adult literature in the classroom. Karina Clemmons is an associate professor of Secondary Education and Laura Langley is a master’s student at University of Arkansas at Little Rock.