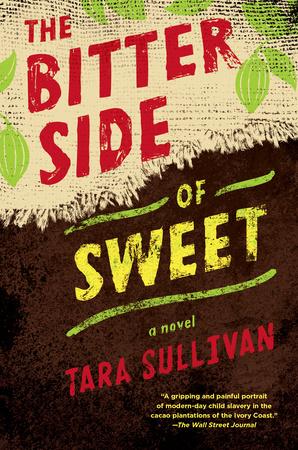

The Bitter Side of Sweet. Tara Sullivan. 2016. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Ages 15+

Summary

The Bitter Side of Sweet, which received four-star reviews from Kirkus, Booklist, Publisher’s Weekly and School Library Journal, tells the story of Amadou, Seydou and Khadija, but in reality it is the story of thousands of children whose names, faces and fates are unknown to us. A word of caution about this young adult novel and its topics—the events in the story are difficult to read about, and readers will likely finish the book with an altered view of the world. In addition, it is a story that will remain with readers for a long time, if not forever.

The Bitter Side of Sweet, which received four-star reviews from Kirkus, Booklist, Publisher’s Weekly and School Library Journal, tells the story of Amadou, Seydou and Khadija, but in reality it is the story of thousands of children whose names, faces and fates are unknown to us. A word of caution about this young adult novel and its topics—the events in the story are difficult to read about, and readers will likely finish the book with an altered view of the world. In addition, it is a story that will remain with readers for a long time, if not forever.

Fifteen-year-old Amadou is from Mali, however, he and his 8-year-old brother, Seydou, find themselves working on a cacao farm in the Ivory Coast. Like many young people from their village, and across Mali, Amadou and Seydou left home to find work as the droughts and poverty that plague the country have made survival a daily struggle. The brothers planned to work for a season in the Ivory Coast and then return to their home and family with their earnings. But that was over two years ago and before they realized that they wouldn’t be workers on a farm, but rather slaves. If someone doesn’t meet the day’s quota, talks back, attempts to run away, or commits any other kind of infraction that person faces a severe beating, withholding of food, other forms of torture, such as being locked overnight in the tool shed, or worse.

Seydou is the youngest on their cacao farm and Amadou, as his older brother, is extremely protective of him. Amadou is also wracked with guilt for what he sees as his part in getting Seydou into this inhumane situation. As a result of this protectiveness and guilt Amadou lets Seydou do very little of the more difficult or dangerous work, especially wielding a machete. Therefore, Amadou must often complete the work of two in order to keep himself and Seydou fed and safe from beatings. And when he isn’t able to do the work of two, he sacrifices his food for Seydou and takes the beatings in his place.

Amadou’s dreams and life change radically as the result of two unimaginable events. The first event, which ultimately leads to the second, is the arrival of Khadija. It’s not unusual for new boys to be brought to the cacao farm to slave away alongside the others. However, they are usually brought in groups—Khadija arrives alone. Most new boys arrive scared and meek—Khadija arrives like a wildcat, fighting, biting, and trying to escape. Finally, in the two years that Amadou and Seydou have been on this cacao farm all the boys who have arrived have been boys—Khadija is a girl, which may be the most shocking part.

Khadija is undeterred and continues her fighting and attempts at escape. During one of her earlier escape attempts Khadija, who has been tied to a cacao tree by one of the bosses, tricks Seydou into getting close enough that she can snatch his machete and cut the rope that binds her. When Amadou discovers what happened he fears for Seydou’s life as the retribution from the bosses for “helping” Khadija escape will no doubt be severe. Amadou quickly assumes the blame for Khadija’s escape and while the bosses are not very convinced by his flimsy explanation of what happened, they are all too happy to punish someone. Amadou is forced to accompany one of the bosses, Moussa, as he tracks and recaptures Khadija. When the three return to camp Amadou receives the most vicious beating of his life.

Amadou is forced to stay and work at the camp, with Khadija, for several days as his injuries are still too bad to allow for him to easily climb cacao trees and chop down the cacao pods. His anxiety over Seydou’s safety is eased slightly by Seydou’s first successful day without him, but it continues to consume him as he tries to get enough work done at camp to impress the bosses and return to their good side. But these efforts are short lived as after a few days of being forced to work at the camp, Moussa returns from the day’s work with news of the second event that radically changes Amadou’s dreams and life. Moussa informs Amadou that he will be returning to work in the fields tomorrow as the crew lost a boy that day. When Amadou asks which boy, Moussa responds “Seydou.”

The rest of The Bitter Side of Sweet tells of their journey to freedom and the horrors, kindnesses and realities they encounter on the way. Khadija shares her story and Amadou begins to understand why she is how she is, but even as he gets to know her better he feels like he knows less and less about her and her life. Along the way they, and the reader, learn more about the cacao and chocolate industry including the vast expanse of land and people, willingly and unwillingly, involved in the business of producing chocolate and the lengths that are gone to for profit and power. After reading this gripping novel chocolate will never taste as sweet.

Cross-Curricular Connections

Social studies/history, geography, economics, journalism, and math

Ideas for Classroom Use

Dying to Tell a Story

As Khadija shares her story with Amadou she explains that she ended up at the cacao farm because she was kidnapped from her home. She also reveals that her mother is a journalist and has been researching a secret topic, one that has prompted threatening phone calls to their home. Khadija believes that there is a connection between her mother’s research and her kidnapping.

Unlike journalists in the United States who have the protection of the First Amendment, journalists in other places around the world often face retribution, threats, and even death as a result of the stories they research and publish. This can happen in the United States as well, but it is more widespread in other parts of the world.

The Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 69 journalists died on the job in 2015. Of these 69 deaths, 47 were victims of murder, with at least 28 of these 47 murder victims receiving death threats before they were killed.

The topics presented above provide a wealth of teaching and learning opportunities. Some of the issues or ideas that can be explored are as follows:

- Freedom of speech is protected in the United States by the First Amendment. What does freedom of speech mean? What protections does the First Amendment provide for freedom of speech?

- What are the topics or stories that have led to the threatening or killing of journalists? What do these topics or stories have in common? What do the threats and/or killings related to these topics or stories indicate about the topics and/or stories?

- In the era of Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms, the reporting of news is changing as is the field of journalism. Is journalism becoming obsolete? What is the role of citizen journalists in this new era?

“I count the things that matter.”

The first line of The Bitter Side of Sweet is “I count the things that matter.” Amadou goes on, “Only twenty-five pods. Our sacks need to be full, at least forty or forty-five each, so I can get Seydou out of a beating. Really full if I want to get out of one too.” Amadou spends his days obsessed with meeting the daily quota of cacao pods in order to protect him and his brother from a beating and hopefully to get them some food for the day.

Quotas rule the lives of many, such as those being paid by piece rate, those working on an assembly line, or those who work on commission. Piecework is when workers get paid a set amount for each item or unit they make or action they perform; for example, a seamstress may get paid for each collar she sews on to a shirt. Although not limited to the jobs held by children, women, and the working poor, the jobs held by these populations often involve quotas, piecework, assembly lines, or commissions.

In order to explore the pressures of working under a quota an assembly line can be created in the classroom. For example, students could assemble a predetermined design out of Legos, with each “worker” adding a specific piece or two to the total. There is an abundance of topics related to this type of work, including:

- What types of industries use assembly lines? Why do these industries use assembly lines? What are the benefits of an assembly line? What is it like to work on an assembly line? Who regulates assembly lines? What does it mean for consumers when they buy products that have been made on an assembly line?

- What industries rely on piecework? Why these industries? What is it like to do piecework? Who regulates piecework? What does it mean for consumers when they buy products that have been made through piecework?

Where Did This Come From?

The world has become a global marketplace; a single product can pass through numerous steps and hands before it arrives at our local store for us to purchase. The Bitter Side of Sweet provides insight into some of the beginning steps and hands involved in the making of the chocolate that we love. Sullivan also provides glances at some of the other steps in the production of chocolate, such as the transport of the dried cacao seeds to large warehouses.

Have students select a product and research the steps involved in its production. Students should consider the “who” involved in each of these steps as well as the “what” of the steps. If a product has steps that occur in different locations, students can create a production map that traces the route of a product and its components as it moves towards completion.

What’s Fair About Fair Trade?

In her author’s note, Sullivan mentions fair trade chocolate. She says, “Fair trade chocolate, produced by companies that guarantee a minimum price to growers even when international prices dip, is by no means the only answer. Nor is it an answer free of its own complications, as any long-term solution must address empowerment and education as well as economics. However, it is one way of tackling the root problem: the grinding poverty of the small growers who produce cacao.” There are many aspects about the idea of fair trade products that can be taught and explored; here are some possibilities:

- What does it mean for something to be fair trade?

- What kind of products can be considered to be fair trade? What do these products have in common?

- What is the impact of fair trade on workers? What is the impact of fair trade on employers? What is the impact of fair trade on consumers?

Additional Resources and Activities

Resources for Teachers: Chocolate Production and Child Slavery: On her website, Tara Sullivan, the author of The Bitter Side of Sweet, provides teaching resources for both of her young adult novels. Sullivan provides suggestions for what readers can do if they have been inspired to action by The Bitter Side of Sweet. She also discusses the idea of fair trade chocolate and supplies a list of other resources on the chocolate industry and modern day slavery.

“The Dark Side of Chocolate”: This 45-minute documentary is a great companion to The Bitter Side of Sweet as it provides visuals for many of the objects, locations, and events that occur in the novel such as the cacao pods themselves and how they are harvested.

Additional Literature With Similar Themes

Diamond Boy. Michael Williams. 2016. Little, Brown.

Iqbal. Francesco D’Adamo. 2003. Atheneum.

Sold. Patricia McCormick. 2006. Hyperion.

Trash. Andy Mulligan. 2010. Ember/Random House.

Aimee Rogers is an assistant professor at the University of North Dakota. She is a member of the reading faculty and teaches children’s literature courses. Aimee’s research interests include how readers make meaning with graphic novels as well as representation in children’s and young adult literature.

Aimee Rogers is an assistant professor at the University of North Dakota. She is a member of the reading faculty and teaches children’s literature courses. Aimee’s research interests include how readers make meaning with graphic novels as well as representation in children’s and young adult literature.