Bullies are a part of life at any age. Bringing the topic to the forefront and leading discussions on bullying as a preventative measure is always better than dealing with a significant bullying incident after the fact. Although bullying is never going to go away, awareness can go a long to way stopping many incidents before they happen. Literature can be a strong venue to help get the topic out into the open.

Bullies are a part of life at any age. Bringing the topic to the forefront and leading discussions on bullying as a preventative measure is always better than dealing with a significant bullying incident after the fact. Although bullying is never going to go away, awareness can go a long to way stopping many incidents before they happen. Literature can be a strong venue to help get the topic out into the open.

Bullying is not an isolated incident but happens over time. The definition of bullying includes three parts: the bullying behavior is intended to do harm, the behavior happens repeatedly and continues over time, and there is an inherent imbalance of power. When we think of bullying we often think about name calling or beating someone up on the playground, but with the growth of the internet the scope of bullying has grown larger. We now have to worry about cyberbullying, including the posting of YouTube videos, Facebook taunts, and viral text messages.

The following are a list of books across grade levels that address the topic of bullying without being didactic. Some are straightforward books that show the impact of face-to-face bullying, and others include the repercussions of online events.

There are a few websites that are excellent resources to find books and activities related to bullying, including choosekind.tumbler.com, www.bulliesinbooks.com, and lesson plans on www.readwritethink.org.

The Engage blog also featured a series on preventing bullying last October. Posts included:

GRADES K-3

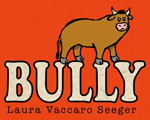

Seeger, Laura Vaccaro. (2013). Bully. New York: Roaring Brook Press.

With the master craftsmanship Seeger is known for, every detail in Bully, from start to finish, tells the story of Bully the bull and his rise and fall from foe to friend. Stark black lines on the cover depict the bold outline of an angry-looking bull. The front endpapers tell his background story; young Bully is bullied by his father. Sometimes the bullied becomes the bully, as Bully diffuses his hurt feelings by hurting others. He goes through the book taunting other animal characters, growing larger and larger on each successive page he bullies others. One day they turn on him and call him “bully,” and Bully sees what he has become. His character shrinks down, barely filling the page, portraying how he has folded in upon himself. This simple-seeming picture book, with its bold lines and stark colors, shows the arc of the bull’s perspective without seeming didactic. Its simplicity makes it the perfect discussion starter for all ages.

With the master craftsmanship Seeger is known for, every detail in Bully, from start to finish, tells the story of Bully the bull and his rise and fall from foe to friend. Stark black lines on the cover depict the bold outline of an angry-looking bull. The front endpapers tell his background story; young Bully is bullied by his father. Sometimes the bullied becomes the bully, as Bully diffuses his hurt feelings by hurting others. He goes through the book taunting other animal characters, growing larger and larger on each successive page he bullies others. One day they turn on him and call him “bully,” and Bully sees what he has become. His character shrinks down, barely filling the page, portraying how he has folded in upon himself. This simple-seeming picture book, with its bold lines and stark colors, shows the arc of the bull’s perspective without seeming didactic. Its simplicity makes it the perfect discussion starter for all ages.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

Dewdney, Anna. (2013). Llama Llama and the Bully Goat. New York: Penguin.

Dewdney’s latest installment of her Llama Llama series tackles the topic of bullying without taking away from the characterization for which she is known. Even though Llama Llama has a lot of school friends, he is the target of Gilroy Goat’s teasing, which makes him feel small. Rather than going straight to a teacher, Llama Llama and his friend first try to stand up for themselves, showing the importance of standing by your friends and working together. Although this is more instructional in tone, this picture book is not overly moralistic but provides a solid base for discussion. The standard rhyming words and rich sharing of emotion make this an accessible book for the preschool age.

Dewdney’s latest installment of her Llama Llama series tackles the topic of bullying without taking away from the characterization for which she is known. Even though Llama Llama has a lot of school friends, he is the target of Gilroy Goat’s teasing, which makes him feel small. Rather than going straight to a teacher, Llama Llama and his friend first try to stand up for themselves, showing the importance of standing by your friends and working together. Although this is more instructional in tone, this picture book is not overly moralistic but provides a solid base for discussion. The standard rhyming words and rich sharing of emotion make this an accessible book for the preschool age.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

Leathers, Phillippa. (2013). The Black Rabbit. Boston, MA: Candlewick Press.

A little rabbit enjoys frolicking outside on a sunny day, until he finds that a great black rabbit is following his every move! He runs from one hiding place to another, trying to outrun the pursuer. But when the little rabbit runs into the woods, he is confronted with another terror, a wolf! How will he survive? Readers will love knowing that the second rabbit is only his shadow, and watch to see how the size of the shadow ultimately scares away the wolf. With just enough fright to keep children on the edge of their seats, the play of light and shadow, depicted in textured watercolors, provides just enough edge for readers to follow the story and come away with a feeling of safety and friendship.

A little rabbit enjoys frolicking outside on a sunny day, until he finds that a great black rabbit is following his every move! He runs from one hiding place to another, trying to outrun the pursuer. But when the little rabbit runs into the woods, he is confronted with another terror, a wolf! How will he survive? Readers will love knowing that the second rabbit is only his shadow, and watch to see how the size of the shadow ultimately scares away the wolf. With just enough fright to keep children on the edge of their seats, the play of light and shadow, depicted in textured watercolors, provides just enough edge for readers to follow the story and come away with a feeling of safety and friendship.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

GRADES 4-5

Starkey, Scott. (2013). The Call of the Bully: A Rodney Rathbone Novel. NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rodney was convinced he was going to have the best summer ever with his friends, until he finds out he has to go to summer camp with the class bully, Josh. Rodney feels betrayed and on edge as he waits for the bullying from Josh to start. But Josh is nothing besides fellow camper Todd Vanderdick, the true camp bully who is protected by his father’s money. When it comes down to Rodney to save the day, he and his friends pull together in one epic moment to save the camp from shutting down. Although the characters and situations are stereotypical, this is a fast-moving read for all struggling readers or fans of Starkey’s previous book.

Rodney was convinced he was going to have the best summer ever with his friends, until he finds out he has to go to summer camp with the class bully, Josh. Rodney feels betrayed and on edge as he waits for the bullying from Josh to start. But Josh is nothing besides fellow camper Todd Vanderdick, the true camp bully who is protected by his father’s money. When it comes down to Rodney to save the day, he and his friends pull together in one epic moment to save the camp from shutting down. Although the characters and situations are stereotypical, this is a fast-moving read for all struggling readers or fans of Starkey’s previous book.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

GRADES 6-8

Patterson, James, Tebbetts, Chris, & Park, Laura. (2013). Middle School: How I Survived Bullies, Broccoli, and Snake Hill. NY: Little, Brown and Company.

The fourth book in the Middle School series shows our hero Rafe ready to tackle summer camp, until he finds out it is not summer camp but summer school camp! He immediately makes friends with his cabin mates, one of whom is brunt of the other boys teasing. Ridiculous happenings ensue, with Rafe ultimately sicking up for his friend. He learns that not everyone is always what they seem from the outside. Told with his signature humor, Patterson puts us in the shoes of Rafe and his hijinks, encouraging gross-out humor and laughter throughout.

The fourth book in the Middle School series shows our hero Rafe ready to tackle summer camp, until he finds out it is not summer camp but summer school camp! He immediately makes friends with his cabin mates, one of whom is brunt of the other boys teasing. Ridiculous happenings ensue, with Rafe ultimately sicking up for his friend. He learns that not everyone is always what they seem from the outside. Told with his signature humor, Patterson puts us in the shoes of Rafe and his hijinks, encouraging gross-out humor and laughter throughout.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

Lawlor, Joe. (2013). Bully.com. Eerdmans Books for Young Readers.

Jun Li likes to fade into the background in his junior high school. He keeps his head down, is quiet, and throws himself into his studies. When he is falsely accused of being the perpetrator of a cyberbullying attack on a popular classmate, Jun either has to prove it wasn’t him or be expelled from school. Jun moves from a unknown student to one in the limelight; one who is now the target of bullying himself. As Jun and his friend work to solve the mystery of the true person behind the cyberbullying attack, they uncover the motivations of why people bully and how bullying may be a protective mechanism in and of itself.

Jun Li likes to fade into the background in his junior high school. He keeps his head down, is quiet, and throws himself into his studies. When he is falsely accused of being the perpetrator of a cyberbullying attack on a popular classmate, Jun either has to prove it wasn’t him or be expelled from school. Jun moves from a unknown student to one in the limelight; one who is now the target of bullying himself. As Jun and his friend work to solve the mystery of the true person behind the cyberbullying attack, they uncover the motivations of why people bully and how bullying may be a protective mechanism in and of itself.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

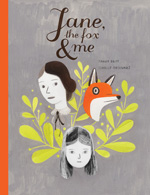

Britt, Fanny. (2013). Jane, the Fox, and Me. Illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault. Translated by Christine Morelli and Susan Ouriou. Groundwood Books.

Originally published in France, Jane, the Fox, and Me is a graphic novel that tells the story of Hélène, a girl who is now ostracized and picked on by her former friends now that she is overweight and has a body odor problem. She finds solace in her favorite book Jane Eyre until the day the bullying goes too far. Hélène begins to believe that what the other girls say about her is true and she sinks into a depression until a new girl moves to town and they begin to form a friendship. The detailed lines of the graphic novel add depth to words and together show a powerful picture of cruelty, friendship, redemption, and learning to believe in oneself.

Originally published in France, Jane, the Fox, and Me is a graphic novel that tells the story of Hélène, a girl who is now ostracized and picked on by her former friends now that she is overweight and has a body odor problem. She finds solace in her favorite book Jane Eyre until the day the bullying goes too far. Hélène begins to believe that what the other girls say about her is true and she sinks into a depression until a new girl moves to town and they begin to form a friendship. The detailed lines of the graphic novel add depth to words and together show a powerful picture of cruelty, friendship, redemption, and learning to believe in oneself.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

GRADES 9-12

Medina, Meg. (2013). Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass. Boston, MA: Candlewick Press.

Piddy Sanchez was a strong student with a bright future until the day someone tells her that the roughest girl in school, Yaqui Delgado, thinks she is stuck up and threatens to beat her up. Piddy finds out that Yaqui doesn't think she is Latina enough, so Piddy becomes the target of vicious verbal and physical threats and it takes over her life. She stops going to school and begins to live in constant fear. After a particularly horrifying episode that was posted on YouTube, Piddy enlists the help of adults as her horror unfolds, but sometimes support simply isn’t enough. Medina’s writing is honest and compelling and pulls us into Piddy’s world as she tackles issues of body image, ethnic and racial identity, safety, and violence. The topics tackled in this book could have lent themselves to the problem novel genre, but Medina was able to tackle serious issues in a sensitive and compelling way.

Piddy Sanchez was a strong student with a bright future until the day someone tells her that the roughest girl in school, Yaqui Delgado, thinks she is stuck up and threatens to beat her up. Piddy finds out that Yaqui doesn't think she is Latina enough, so Piddy becomes the target of vicious verbal and physical threats and it takes over her life. She stops going to school and begins to live in constant fear. After a particularly horrifying episode that was posted on YouTube, Piddy enlists the help of adults as her horror unfolds, but sometimes support simply isn’t enough. Medina’s writing is honest and compelling and pulls us into Piddy’s world as she tackles issues of body image, ethnic and racial identity, safety, and violence. The topics tackled in this book could have lent themselves to the problem novel genre, but Medina was able to tackle serious issues in a sensitive and compelling way.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

Hubbard, Jennifer. (2013). Until it Hurts to Stop. New York: Penguin.

Throughout middle school, Maggie was bullied mercilessly by her schoolmates and was at the bottom of the school social order. She grew to accept the taunts, that she is pathetic, ugly, stupid, and unworthy of true friendship. Now Maggie is a junior in high school, and although her primary tormentor had moved away years ago, she is always prepared for another attack. The only time she feels safe is when she is out hiking with her best friend Nick, but lately, Maggie has been developing feelings for him. How can she expect him to ever love her if she doesn’t love herself? This novel is powerfully written, and the Maggie’s words haunt the mind. The reader walks in Maggie’s shoes and experiences the fear, heartbreak, and hope as Maggie progresses through the story.

Throughout middle school, Maggie was bullied mercilessly by her schoolmates and was at the bottom of the school social order. She grew to accept the taunts, that she is pathetic, ugly, stupid, and unworthy of true friendship. Now Maggie is a junior in high school, and although her primary tormentor had moved away years ago, she is always prepared for another attack. The only time she feels safe is when she is out hiking with her best friend Nick, but lately, Maggie has been developing feelings for him. How can she expect him to ever love her if she doesn’t love herself? This novel is powerfully written, and the Maggie’s words haunt the mind. The reader walks in Maggie’s shoes and experiences the fear, heartbreak, and hope as Maggie progresses through the story.

- Melanie Koss, Northern Illinois University

These reviews are submitted by members of the International Reading Association's Children's Literature and Reading Special Interest Group (CL/R SIG) and are published weekly on Reading Today Online. The International Reading Association partners with the National Council of Teachers of English and Verizon Thinkfinity to produce ReadWriteThink.org, a website devoted to providing literacy instruction and interactive resources for grades K–12.