Two years ago my life changed with a cocktail napkin at a dyslexia conference in Baltimore. I spent two days listening to Peter Bowers, the founder of

The WordWorks Literacy Centre in Ontario, Canada, and Gina Cooke, the author of the blog

LEX: Linguist-Educator Exchange, in the booth next to me, talking to dozens of people about something that just sounded like “another program for those with dyslexia.”

But after two days, I figured all those people talking to Peter and Gina with such newfound enthusiasm must be on to something. I turned to Peter and said, in my most skeptical voice, “Okay, tell me what all this hullabaloo is about.” He simply wrote the word “sign” down on a napkin and then created this word sum for me:

sign + al = signal

Then he asked me what I noticed about the “g” in the new word. That’s when it hit me: The word “sign” is not a sight word. The “g” is there to mark its connection to “signal,” “signature,” and “resign.” In fact, there is no such thing as a sight word. English makes sense.

We’ll get to specific classroom strategies in a moment, but it’s important, first, to look at the foundation for “real spelling.”

Decades ago, both Carol Chomsky (in the Harvard Educational Review in 1970) and Richard Venezky (in Reading Research Quarterly in 1967 and The American Way of Spelling in 1999) put forth very informative and compelling reasons for teaching the English language the way it was meant to be understood. Their description of English spelling offered educators everything we needed to know to dispel the rampant misunderstanding in classrooms everywhere, that the written language is supposed to be a sound/symbol representation, and that any word that deviates from this belief is an “exception” or a “red, sight, or crazy” word that just needs to be memorized. They explained grapheme/phoneme understanding is still critically important to understanding the language, but we cannot possibly know how a word will be pronounced (or read) until we know how it appears within a grammatical and morphological context. Venezky said, “…the simple fact is that the present orthography is not merely a letter-to-sound system riddled with imperfections, but, instead, a more complex and more regular relationship wherein phoneme and morpheme share leading roles.”

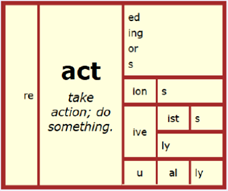

I was starting to notice an underlying structure of English and was ready to take on some more of my long-held assumptions about English orthography. I analyzed more word sums and found the true suffix is the Latinate “-ion,” not “-tion” and “-sion.” Here is an easy word to illustrate this orthographic fact: the word “action” has the base “act” and the suffix “-ion” which is illustrated in this word sum: “act” + “-ion” à action. If we suggest the hypothesis is that the suffix is “-tion” and put it into a word sum to test that hypothesis, we get “ac” + “-tion” and I realized that “ac” cannot be the base. The base has to be “act,” and therefore the suffix has to be “-ion.” With this new information I could then build a matrix for a whole family of words related in meaning and spelling to the base “act,” but like “sign,” the base had different pronunciations depending on what suffix was added!

Shown here is a word matrix to help illustrate the concept (created with the free mini-matrix maker):

In this one matrix the student would have learned the grapheme “t” can represent different pronunciations depending on its place in a word. Think “actual” and “acting.” With this one matrix a student understands 23 words and the underlying principle of “-ion” which makes hundreds of other words available to them.

Now, back to the “-ion” suffix. Would it not be a better approach to teach all students– including those with dyslexia how the language works rather than having them guess which one says /ʒən/ and which one says /ʃən/ For argument’s sake, try this word on for size: the word “tension” is represented in a word sum as “tense/” + “-ion” à tension. The single silent “e” is replaced by the vowel suffix “-ion.” It’s a simple suffixing pattern. Some students understand this logic more easily and are able to understand it early, given the opportunity.

In the case of students with dyslexia, orthographic instruction still responds to the need for morphophonemic awareness, it responds to the explicitness needed, it is multisensory and, best of all, it accomplishes our goal with a boatload of rhyme and reason along with enough critical thinking to make the Common Core authors jump for joy.

Homophones Set the Tone

Introducing the concept that spelling is meaning-based versus sound-based can be accomplished with an introduction to homophones. The homophones <see> and <sea> are a great place to start. I simply write the words down next to each other and ask the student to announce the word, which means they tell me the letter names, not the sounds they ‘make' and they do not try to sound out the word, they only tell me the letters in the words. Once they verbally announce the letters they are then prompted to pronounce the words. If they are unable to do so, I tell them the word. I then ask them to analyze each word and tell me if they are spelled the same. Once they identify that the spellings are different, I then ask them what each word means. Finally, they hypothesize why they think the words are spelled differently despite being pronounced the same. Students, including students with dyslexia, understand that they are spelled differently because they mean different things. Bingo…they understand the concept. This is also a jumping off point to point out that we already see two different graphemes <ee> and <ea> that can represent the /e/ phoneme.

My student is then encouraged to keep a list of homophones learned as he or she encounters them. Other homophones that can be used for this introductory activity are: hear/here, to/too/two, where/wear. Each pair has a rich etymological history that you can investigate with your student to find out why they are spelled differently.

Teach Grapheme/Phoneme Options

We should not say, <f> says /f/ like in fun. First of all, letters do not talk. Secondly, students need to understand that most phonemes can be represented by more than one grapheme and /f/ is the perfect example. We often teach phonemes by targeting just one grapheme that represents it. So, if we want to target the /f/ phoneme, we might use words starting with <f> and say something like, “<f> is for /f/ like in <fun>.” But given that instruction, what is a child supposed to make of words like <laugh> or <phone>? One option is to simply say, “One way of writing /f/ is with <f>.” That may spark children to ask “What are some other ways?” You could then share words like <leaf>, <fun>, <knife> and <phone>, <graph> and <rough>, <laugh> and use them to investigate three ways of writing /f/. In this way, the child is not taught in such a way to think that words like <laugh> and <phone> are “tricky.” Studying spellings becomes an investigation not memorization and this particularly important for students with dyslexia who are already using extra cognitive effort to read and spell. Students can create sound option charts. They add to the chart as they investigate and encounter new words. Below is an example of a sound option chart for the phoneme /f/:

| phoneme

/f/ | <f>, <ff>: stiff, leaf, fun, find, knife |

| <ph>: phone, gopher, dolphin |

| <-ugh>: rough, cough, laugh, enough |

The student finds the words for the sound option chart by looking through literature or simply adding the words as they notice them. This is a living document and students will continuously add new words. For students with dyslexia, this creates a sense of organization and predictability they need. (For more in-depth activities, visit Beyond the Word.)

This is just the tip of the iceberg—and I mean the very tip. If I had 10 more pages, I would just be getting started. I hope you had at least one aha moment and I hope this has left you with many questions or motivated you to learn more to become more fluent in English orthography and teaching orthography. For published research on this understanding of English spelling and instruction, you can start here. Then, take a look at some of these free resources:

Kelli Sandman-Hurley (dyslexiaspec@gmail.com) is the co-owner of the Dyslexia Training Institute. She received her doctorate in literacy with a specialization in reading and dyslexia from San Diego State University and the University of San Diego. She is a trained special education advocate assisting parents and children through the Individual Education Plan (IEP) and 504 Plan process. Dr. Kelli is an adjunct professor of reading, literacy coordinator and a tutor trainer. Kelli is trained by a fellow of the Orton-Gillingham Academy and in the Lindamood-Bell, RAVE-O and Wilson Reading Programs. Kelli is the Past-President of the San Diego Branch of the International Dyslexia Association, as well as a board member of the Southern California Library Literacy Network (SCLLN). She co-created and produced “Dyslexia for a Day: A Simulation of Dyslexia,” is a frequent speaker at conferences, and is currently writing “Dyslexia: Decoding the System.”