Maybe it’s just me, but it seems like today’s students are being asked to read more nonfiction and compose more “informational” writing than ever.

The NCTE/IRA Standards for English Language Arts advocate for classrooms where students gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of print and nonprint sources (Standard #7). The Common Core College and Career Readiness Anchor Standard for Reading (#1) asks students to “cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.” The CCSS Anchor Standards for Writing (#7-10) stress that students need to be able to conduct short and more sustained research using multiple print and digital sources and to participate in shared research projects.

If your students are like mine, most of them are doing the majority of their research online. And, if yours are like mine, they could use a little help. I’ve found that my students appreciate being introduced to tools that help them manage and organize the information that they’re finding. The good news is that there is a plethora of new tools available. Recent IRA TILE-SIG blog posts have touched on some useful applications for annotating online text. In “Using Apps to Extend Literacy and Content Learning,” Jill Castek discussed the app DocAS, as a way to mark up reading materials to show students’ emerging ideas. And in “Literacy Practices Through the UDL Lens, Part 2,” teacher Monee Perkins noted that her seventh grade students use Adobe Reader’s annotation feature to address complex text and provide them with another representation for text commenting.

I’d like to add a few online annotation tools that I’ve used in my teaching and in my own research that are worth a look.

Citelighter

My favorite new app to use with my students is Citelighter because it combines the ideas of social bookmarking, note-taking, and citation-managing with some promising teacher tools.

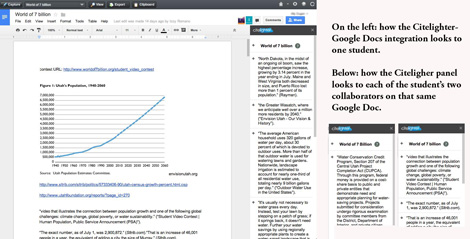

The students in my media production class used Citelighter to help them manage information they found while creating a Public Service Announcement about water use issues in our community. As each student in the group examined different perspectives on the issue, Citelighter’s browser toolbar allowed them to highlight, annotate, cite, and comment on important information as they found it. It even synced with their shared Google Doc so that their knowledge was constructed seamlessly (see graphic below). The students said that it made their collaboration easier. Additionally Citelighter’s citation feature formats sources in either APA, MLA, or Chicago style without the errors that happen on a lot of online citation formatting websites that my students have used in the past.

My students are excited about features that will streamline their own workflow, but there are some other things about Citelighter that interest me as a teacher. The student profile panel tells me not only the citations my students are generating in their research, but also how many sources they’re citing from. This helps me when conferencing with the students about ways that they might improve their research strategies.

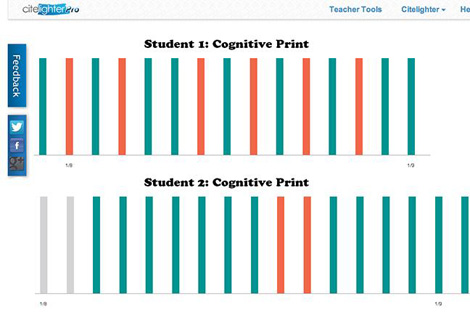

Citelighter also creates a “Cognitive Print” of the students’ progress on a particular writing assignment. The image below shows the different ways two students approach the composition process while researching. Student 1’s Cognitive Print shows a more consistent pattern of copying from sources followed immediately by writing and annotating. Student 2’s Cognitive Print shows longer periods of gathering of information and then writing about that information in one bigger block of time. Neither approach to the research process is “right,” but this information gives my students and me something more to conference about, and provides more information for their own self-reflection.

Diigo

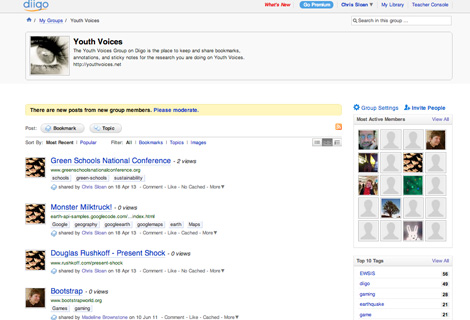

Diigo is a social bookmarking service based on the idea that when you bookmark a website on your computer, it’s only useful if you’re actually on that same computer. Social bookmarks, on the other hand, carry over to any computer as long as you’re logged in to a service like Diigo or Delicious. But even more powerful is the fact that you can share your bookmarks with others, and you can see what other like-minded people are bookmarking. Features like this facilitate social scholarship. Some colleagues in the National Writing Project and I have our students discuss their digital compositions on Youth Voices, and sharing bookmarks through Diigo gave us another way to collaborate (see graphic below). For practical ideas on how to implement Diigo in classroom settings, see Ferriter and Garry’s book, Teaching the iGeneration.

Crocodoc

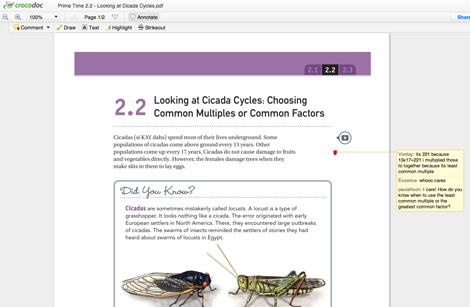

Crocodoc converts Word or PDF documents to allow for collaboration via the web. Users can highlight key passages, share them with collaborators, and even send others the link to the annotated document. Crocodoc is similar to DocStoc or Scribd, but because it’s created with HTML5 (and not Flash) it works well not only with modern browsers, but also Apple’s iPads and iPhones. New York City teacher Paul Allison has his 7th graders use Crocodoc primarily to annotate readings and as another way to discuss course content.

Mendeley

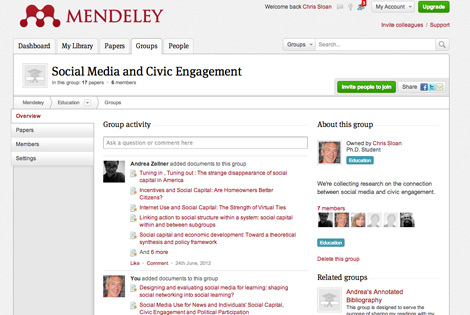

When some members of my doctoral studies cohort and I were researching social media and civic engagement, we shared our findings with each other via Mendeley, a reference manager and PDF organizer. Mendeley is particularly useful for the kind of academic research done in graduate school. For example, when I would come across a journal article that I thought my collaborators would find useful, all I had to do was drag and drop the article on to the icon on my desktop; in addition to making it easier to share research, the program extracts the title, journal, keywords, and other relevant information. There’s a plugin available for Microsoft Word to make citing sources much easier in that application. Zotero also has many of these same features listed above. For an excellent example of Zotero in the college classroom, see Ballenger’s The Curious Researcher.

Educators have known about the benefits of active reading for a long time; reading research has shown what effective comprehension strategies can mean for learning. Some of the best pre-Internet teachers I’ve known had their students read with a “pencil in hand”—making notes in the margins of their pages, judiciously annotating key passages, composing their thoughts in dialectical journals, and then sharing their findings in classroom discussions. Students now are doing their research online, and the habits of mind that good readers have always brought to bear on text can be facilitated through the use of new applications.

Chris Sloan teaches high school English and media at Judge Memorial in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is also a PhD candidate in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology at Michigan State University. Join him on the Teachers Teaching Teachers webcast every Wednesday at 9:00 p.m. Eastern Time at teachersteachingteachers.org.

Chris Sloan teaches high school English and media at Judge Memorial in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is also a PhD candidate in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology at Michigan State University. Join him on the Teachers Teaching Teachers webcast every Wednesday at 9:00 p.m. Eastern Time at teachersteachingteachers.org.