As a former ancient history teacher, I occasionally receive resource requests from former colleagues. I was prepping a collection of my old materials for a friend this week and came across a WebQuest I designed several years ago. In it, students explore the achievements of four Mesopotamian empires and then design a proposal for a new exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. It was one of my favorite assignments, as it fostered the development of online reading comprehension and public speaking skills in a digital inquiry setting.

As a former ancient history teacher, I occasionally receive resource requests from former colleagues. I was prepping a collection of my old materials for a friend this week and came across a WebQuest I designed several years ago. In it, students explore the achievements of four Mesopotamian empires and then design a proposal for a new exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. It was one of my favorite assignments, as it fostered the development of online reading comprehension and public speaking skills in a digital inquiry setting.

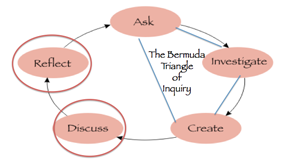

Now a second-year doctoral student, I’ve given quite a bit of thought to the inquiry process over the last year. One approach I like to use is the Inquiry Cycle, as highlighted by Ann P. Bishop and Bertram C. Bruce, which features five actions: Ask, Investigate, Create, Discuss, and Reflect. While depicted as a cycle, Bruce and Bishop are quick to note that inquiry does not take a neat, orderly process—the cycle is merely suggestive, not absolute. Sharing the WebQuest with a colleague allowed me the opportunity to reflect on the project with fresh eyes.

The challenge of inquiry-based instruction

Though proud of the task, I would revise it further as it reflects an issue that often comes up when using inquiry-based learning in schools; one I like to call the Bermuda Triangle of Inquiry. For those unaware of the Bermuda Triangle, it’s an area of the Atlantic Ocean marked by geographic points of Miami, Puerto Rico and Bermuda, where planes and boats have inexplicably become lost throughout history.

In the Bermuda Triangle of Inquiry, tasks also can become lost, but in the Ask, Investigate and Create phases. Projects are sometimes unable to sustain themselves through to the Discuss or Reflect destinations. My Webquest project is a prime example of a task caught in the Triangle. After moving through the first three phases, students shared their findings via the presentation, but I didn’t provide a space for discussion. Furthermore, students were not asked to reflect on their findings or given the time to think about ideas from their classmates. After the presentations were given, the projects disappeared and, along with them, the opportunities for further thinking and exploration.

Shifting our inquiry-based instructional practices

We can begin to address this problem by making two shifts in how we approach inquiry learning. First, the creation portion of any inquiry could be viewed not as the end product of the Inquiry, but rather a jumping off point for discussion. I’d suggest we look at creating from the constructionist’s vantage and see it as Pete Skillen wrote, part of “making one’s own mind.” Thus, the goal is not simply the creation of something, but also the sharing and discussion that follows, which allows us to “make” or “create” knowledge while reflecting on the conversation.

Secondly, we could change the primary goal of inquiry from finding the correct answer to finding one’s next question, as suggested by Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown. Through discussion and reflection new questions can emerge. These questions can be shared and developed with peers for further discussion, reflection and exploration, which ensures that the cycle continues. Thus, the focus of inquiry becomes continuing the exploration, and not necessarily finding its end.

Possible Action Steps

So how might we change our practice to incorporate these fixes? Using my Mesopotamian Empire project as an example, I might have my students create a blog or a podcast asking them to reflect on their findings, choices and processes used to research and create their product. Their classmates would then be asked to read / listen and respond to their classmates’ work and ideas, providing suggestions or questions to consider for the next cycle of inquiry. In subsequent inquiry projects, students would be asked to use their peers’ feedback to guide their process. End reflection questions should ask students how they incorporated previous experiences and peer suggestions into their inquiry process. Texts like Teaching in the Connected Learning Classroom provide additional ideas for ways to enable students to discuss and reflect on their learning.

The second shift, from Inquiry as finding answers to Inquiry as finding questions, may be a bit more challenging. It requires teachers to provide students with more latitude on content and it also requires students to take ownership of their learning. This autonomy necessitates open inquiry, but without navigation and critical evaluation skills, students will likely struggle to find answers and generate new questions. Most of all, it requires a teacher’s most precious resource: time. Frameworks like Genius Hour and Design Thinking provide useful frameworks that give structure and constraints for students to explore their interests organically. These approaches, combined with direct instruction in online reading comprehension provide the right supports and constraints to steer clear of our infamous Triangle!

Dave Quinn is a doctoral student in the URI/RIC Ph.D. in Education program. Previously, he was a history teacher at King Philip Middle School in Norfolk, MA and a member of the Seekonk School Committee. He can be reached at David_Quinn@my.uri.edu.

Dave Quinn is a doctoral student in the URI/RIC Ph.D. in Education program. Previously, he was a history teacher at King Philip Middle School in Norfolk, MA and a member of the Seekonk School Committee. He can be reached at David_Quinn@my.uri.edu.

This article is part of a series from the International Reading Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).