As a literacy teacher for nearly 25 years, I’ve seen many trends ebb and flow, each one seeking to enhance lifelong learning. Cornell notes. Dialectical journals. Writer’s workshop. Visualization. One-page diagrams. Mind mapping. Freytag Pyramid. Transactional reader response. As Julie Coiro notes, literacy tools of all kinds motivate students, to “wonder, anticipate, explore, and think deeply about things that matter to them.” With each “new” movement, a kernel of what came before is carried along.

Digital literacy practices in today’s classrooms and out-of-school learning centers incorporate some of the best literacy learning across domains, platforms, and practices, such as Microsoft and Google environments, blogs and websites, coding and filmmaking, digital storytelling, and portfolios.

And, yet, digital literacy is also a bit different than other types of literacy. It’s a very hands-on learning experience. Although it is possible to acquire the skills and strategies of digital competence through reading a how-to tech text, the likelihood of digital mastery increases with 1-to-1 instruction. This makes sense, as all learning is social. Let’s look at some examples to get you thinking about the possibilities.

And, yet, digital literacy is also a bit different than other types of literacy. It’s a very hands-on learning experience. Although it is possible to acquire the skills and strategies of digital competence through reading a how-to tech text, the likelihood of digital mastery increases with 1-to-1 instruction. This makes sense, as all learning is social. Let’s look at some examples to get you thinking about the possibilities.

Could Google Sites such as mine be useful for modeling how electronic portfolios can support learning? Or maybe you’re interested in exploring how Padlet or Socrative can be used to develop quick formative assessments? Perhaps Piktochart (such as this project) or Canva more closely approximate commonly-accepted conventions of 21st-century text rather than markers and a paper poster board?

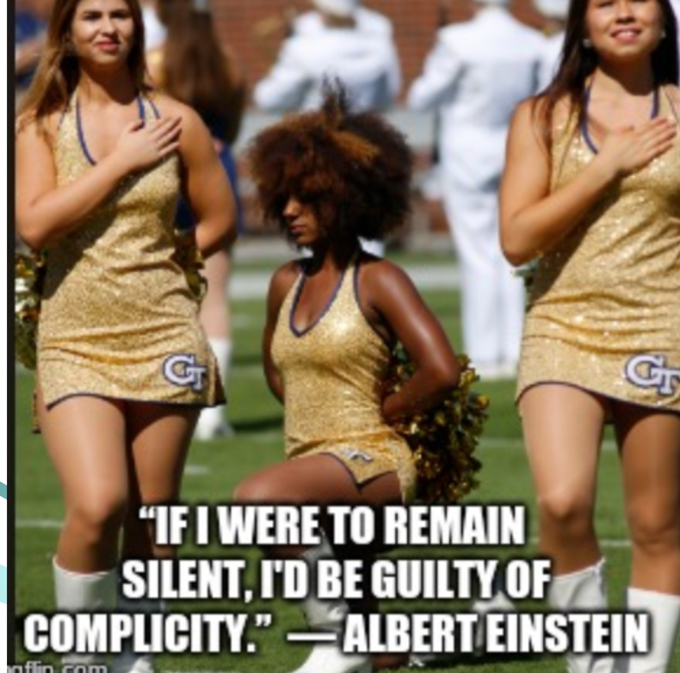

Would Storybird increase student engagement in ways that worksheets can’t, as students learn how to identify narrative structure—such as in this poignant student-created children’s book about gender equality? Or are memes a better way to teach metaphorical language and symbolism than mining a text for an author’s meaning? You can see how I modeled memes in the mashup below for my Sports and Popular Culture course during a unit on race and class.

It’s likely that the answer to at least some of these questions is yes. But I believe the most efficacious way to translate the ability to navigate each of the platforms is person to person. The digital educator is a facilitator, spreading expertise in what begins as small pockets of individual epiphanies into currents of students teaching each other.

It’s likely that the answer to at least some of these questions is yes. But I believe the most efficacious way to translate the ability to navigate each of the platforms is person to person. The digital educator is a facilitator, spreading expertise in what begins as small pockets of individual epiphanies into currents of students teaching each other.

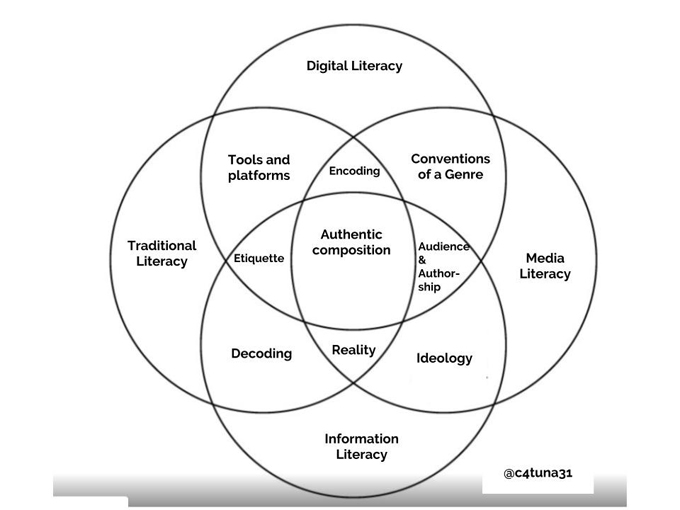

The domains of literacy merge and recede, too, so that digital literacy meets and extends other types of literacy learning. With the help of digital tools, informational literacy, media literacy, and traditional literacy speak to each other vividly. Indeed, a new-and-improved type of mastery learning, asynchronous digital literacy, invites in all kinds of learners to take advantage of tools that weren’t available to previous generations who relied on pen and paper, print textbooks, and the sole option of face-to-face instruction.

Rather than seeing digital instruction as an additional expectation for educators, I’d like to suggest that expertise in digital tools and texts eases an educator’s multiple and frequently contradictory responsibilities. When the educator is a facilitator whose models can be hyperlinked, for example, all kinds of learners and learning experiences become possible. Students and educators are able to investigate (as shown in this mental illness WebQuest for a psychology and literature course), collaborate (students worked together in teams to analyze The Zoo Story), and reflect (I created a teacher model for a film assignment on a “sense of place”). A more nuanced toolkit of literacy strategies has the capacity to stick with students after an individual lesson or even course ends, as digital literacy seeps from one classroom to everyday textuality.

Rather than seeing digital instruction as an additional expectation for educators, I’d like to suggest that expertise in digital tools and texts eases an educator’s multiple and frequently contradictory responsibilities. When the educator is a facilitator whose models can be hyperlinked, for example, all kinds of learners and learning experiences become possible. Students and educators are able to investigate (as shown in this mental illness WebQuest for a psychology and literature course), collaborate (students worked together in teams to analyze The Zoo Story), and reflect (I created a teacher model for a film assignment on a “sense of place”). A more nuanced toolkit of literacy strategies has the capacity to stick with students after an individual lesson or even course ends, as digital literacy seeps from one classroom to everyday textuality.

Think of all the ways that our students are composing today. As a social constructivist digital space, YouTube's Which University gives youth voice to compose and publish. The mash-ups so popular on social media connect cultural allusions to contemporary current events. In a 2013 article How Media Literacy Supports Civic Engagement in a Digital Age, researchers Hans Martens and Renee Hobbs discuss how media literacy supports civic engagement by explaining how civic engagement has been revived by the commenting feature of online magazine and newspapers. Each of these composition and publishing practices requires a facility with digital literacy that is acquired through what researchers Christine Greenhow and Kathy Lewin call social modeling.

Digital literacy that emphasizes learners as coproducers of knowledge has a strong focus on students’ everyday use of and learning with Web 2.0 technologies in and outside of classrooms. Social digital learning imbues classrooms with challenges for students to interact, share information and resources, and think critically. With its inherent increased levels of peer support and communication about course content and assessment, digital learning is a win-win scenario, offering positive effects on the expression of self and voice across disciplines and intelligences.

Carolyn Fortuna, PhD, is the program chair of the Northeast Regional Media Literacy Conference and professional development coordinator for the Media Education Lab. You can follow her digital and media literacy work at idigitmedia.com.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).