The NMC/CoSN Horizon Report: 2017 K–12 Edition identifies "Advancing Cultures of Innovation" as a key trend toward accelerating innovative technology adoption in education. In these cultures of innovation, learner-centered classrooms provide space for students to conduct research, collaborate, and create in real-world contexts.

While integrating technology can increase student engagement, this integration must be done in a purposeful way. With the lack of appropriate and timely professional development, this can be difficult to conceptualize. Although more classrooms are receiving digital tools, and many teachers want to be able to use these tools in an authentic, targeted manner, a nationwide survey conducted by Samsung has shown that 60% of teachers say they need more training to do so.

Although blogs such as Literacy Daily do not replace the need for professional development, they do allow us to share ideas that have worked in our classrooms so other educators can adapt and implement to fit the needs of their students. With this in mind we share how Abigail, a teacher candidate, integrated science, language arts, and technology in her fifth-grade classroom this spring.

Mapping the ocean floor with Bloxels

When asked to design a lesson on ocean floor landforms, Abigail decided she wanted to do so in a way that would purposefully integrate technology and authentically engage students. She did this by providing fifth-graders with the opportunity to build a digital model of the ocean floor using Bloxels, a digital platform for creating video games in the classroom.

After a brief mini-lesson, each of Abigail’s five groups worked together to research their assigned ocean floor landform: continental shelf, continental slope, abyssal plain, mid-ocean ridge/rift zone, and trenches. Groups used books, articles, and credible online sources to conduct research. Each student was given a research log to organize their learning.

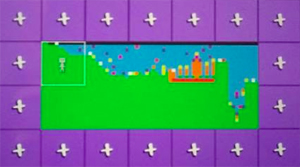

Once the groups had gathered enough information about their ocean floor landform, each table was given a Bloxels design sheet. The small groups collaborated to take what they learned about the ocean floor landform and create a design for the Bloxels video game. Students used different colors to represent different features such as blue for water, green for terrain, purple for an enemy, and yellow for a coin. Designs were creative and scientifically accurate.

Students then translated self-guided, landform research into unique features for their portion of the game. One group researched what kind of sea creatures lived in their part of the ocean in order to select one as an enemy. After learning that seashells were commonly found in their section of the ocean floor, another group decided the coins in the video game would be seashells. The mid-ocean ridge/rift zone group included exploding orange blocks to represent underwater volcanoes.

Learning about landforms

Next, each group shared their learning about the landform they studied. The class compared Bloxel design ideas to a diagram of the ocean floor and gave each other feedback. Each group designed one portion of the ocean floor, one column comprised of two boxes, that when combined formed the complete ocean floor (see the above image). For example, the continental shelf group found that their landform is a gently sloped piece of the continent that shifts land to sea. This group’s contribution to the video game can be seen in the first column; notice the player begins on continental shelf. When the game starts, the player zooms in here and navigates through each component of the ocean floor. The player must make it all the way across the ocean floor and out of what can be seen in the last column, the trench. The group that researched trenches learned that landform is long, narrow, and is the deepest part of the ocean floor.

The groups went back to their working stations, revised their designs, and transferred their landform model to the Bloxels app. Each group was required to include at least one white text box that identified the landform and explained its key characteristics.

At the end of this integrated learning segment, students had conducted research and collaboratively designed and refined a video game to represent their understanding of the ocean floor. Students were engaged from beginning to end. They shared their learning with the class through discussions and with the teacher through detailed exit tickets that provided a clear snapshot of individual student learning. Through research and collaboration, students, motivated to build a video game, went above and beyond the teacher’s expectations by adding details such as making the player’s enemy a research-based creature from that specific ocean landform zone.

Other ideas for incorporating video game building in the elementary classroom include: rewriting the ending of a book, writing math problems that players must solve to progress through the game, and creating a storyline in which a soldier must move through each of the major WWII battles.

Lindsay Yearta is an assistant professor of education and the Singleton Endowed Professor at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Her research interests include digital literacies and the utilization of technology to empower students. You can find her on Twitter @Lyearta.

Abigail Wenger is a rising senior at Winthrop University. She is studying early childhood education and will complete her year-long internship in a kindergarten classroom in the coming school year. You can find her on Twitter @Ms_Wenger.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).