Earlier this fall, I was scrolling through Twitter when I came across an anchor chart created by Pana Asavavatana. Hashtagged with #MentorTech and #LivBit, I curiously clicked on the handle of @TheLivBits. Short for Olivia, Liv is an elementary student in the United States who shares selfie videos that range from book reviews to her thinking about reading. Liv also shares meetings with authors and inspirational bits.

Earlier this fall, I was scrolling through Twitter when I came across an anchor chart created by Pana Asavavatana. Hashtagged with #MentorTech and #LivBit, I curiously clicked on the handle of @TheLivBits. Short for Olivia, Liv is an elementary student in the United States who shares selfie videos that range from book reviews to her thinking about reading. Liv also shares meetings with authors and inspirational bits.

In an age of global connectedness, Liv’s videos, shared through her “mom-monitored” Twitter, Instagram, and Vimeo accounts have taken the world by storm since she began posting in February 2016. Curious about the possibilities of using Liv’s videos in the global literacy classroom, I reached out to Pana and asked her to share her strategies for doing so.

Pana is the preK–2 technology and design coach at Taipei American School, an independent, coeducational day school with a U.S.-based curriculum. Founded in 1949 for preK–12 learners, its students represent more than 30 nationalities. In her role, Pana collaborates with 23 teachers as well as specialist teams, including Mandarin and art, with a focus on technology integration, robotics, and engineering.

An active Twitter user, Pana first encountered Liv through teacher and author Kristin Ziemke, who had posted about #LivBits. Pana discovered Liv’s Instagram (note: the account is private and you must request permission to follow), where Liv began her journey of sharing ideas about books. During summer 2016, Pana, Kristin, and Liv met at the Building Learning Communities (BLC) education conference in Boston, where each person presented.

As many of us know, “literacy” is more than just reading text on a page. Communicating in today’s world includes multisensory, multimodal, and interactive experiences to engage audiences. What does this mean for teachers and students?

Together, we must learn to think critically about new media and how to use it effectively to share ideas globally. Liv is one example of a student connecting with wider audiences using digital platforms, which reflects the evolving nature of communication today.

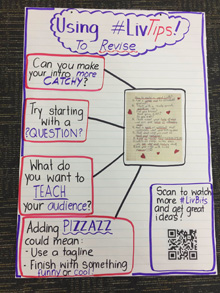

Mentor texts in literacy teaching are not new. We, as educators, often use them to teach craft or techniques in writing and hope our students will use these tools to enrich their own writing. Similarly, Liv’s videos act as “mentor tech” and provide models that Pana’s students use to create their own videos. Pana’s students begin drafting a script before filming their first video and then revising their work. Throughout this process, students watch several versions of Liv’s videos, noting craft techniques they might borrow—from what they might say to how ideas are presented on camera.

The collaboration between Pana and Liv is but one example of how new technologies are continually opening new doors for fostering a global literacies network, inclusive of both teachers and children. As Liv’s mom shared with me, Liv’s goal is “to be a positive voice for kids, to celebrate others’ work, and to grow advocacy for causes she cares about—like being a voice for shark education.” The selfie videos created by Liv and Pana’s students provide teachers another medium for generating meaningful assessment, feedback, and communication that tells much more about a child’s literacy learning than a test score.

Liv is one model of how children can use social media not only to learn but also to develop, reflect on, and share their passion and knowledge with others as they cultivate metacognition about their literacy experiences.

Special thanks to Pana Asavavatana, an Apple Distinguished Educator, for connecting with a stranger from across the globe via Twitter. I am deeply grateful for her willingness to share her teaching expertise and the work of her students at Taipei American School with me.

Cassie J. Brownell is a doctoral candidate and Marianne Amarel Teaching and Teacher Education Fellow in the Department of Teacher Education at Michigan State University. A corecipient of a 2015 NCTE-CEE Research Initiative Grant, Cassie’s most recent collaborative project—#hearmyhome—explores how writing with and through sound might help students and teachers attune toward literacies and communities of difference.

Cassie J. Brownell is a doctoral candidate and Marianne Amarel Teaching and Teacher Education Fellow in the Department of Teacher Education at Michigan State University. A corecipient of a 2015 NCTE-CEE Research Initiative Grant, Cassie’s most recent collaborative project—#hearmyhome—explores how writing with and through sound might help students and teachers attune toward literacies and communities of difference.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).