A recent article titled, “Hey Prof, no one is reading you,” highlights the dilemma of literacy professors whose annual evaluations depend on publishing research in peer-reviewed academic journals. Such journals are rarely, if ever, read by or written in language for practitioners, parents, elected officials, or the public at large. So how does one meet university tenure and promotion expectations and concurrently share research findings meant to impact what happens in local schools, families, and communities?

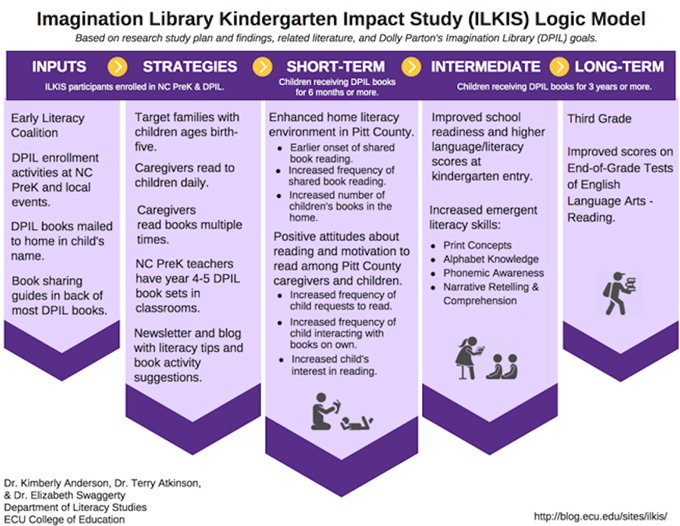

In the midst of a community literacy coalition initiative launched by our local United Way chapter, our university research team wrestled with how to share our related research outcomes with a range of audiences. Invited by the coalition to conduct a five-year study documenting the impact of Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library on kindergartners’ school readiness, we were asked to share our findings with elected officials, university groups, and community audiences. Thus, we shifted from writing research grants and articles in academic language to creating at-a-glance snapshots of our research findings. As is often the case when found in a bind, we dove into uncharted water with tech tools that served as lifelines as we sought to simplify, summarize, and share our work with community partners.

Knowing that we needed both web and print media design and graphics, we looked to Edutopia blogger and assistant editor Todd Finley, who recommended Canva as one of the most user-friendly free graphic design sites around. Indeed, Canva design layouts offered options for documents, social media graphics/posts, blogging/E-books, marketing materials, email headers, event announcements, and ads, enabling us to transform narratives into graphic outcomes such as:

- A quarterly newsletter, which offers advice to parents/guardians of Imagination Library enrollees, based on needs identified in our study.

- An Imagination Library introductory flyer, available in English and Spanish, that’s given to parents/guardians of new enrollees at community events/Vidant Medical Center.

- A visual display of findings from our baseline publication.

Our next on-the-spot request arose while completing a grant application to secure additional funding. A project website URL was required for submission. With a short deadline in mind, we used the WordPress blog format (supported by our university, but also available free online) and integrated our existing Canva graphics to launch an Imagination Library Kindergarten Impact Study (ILKIS) website. Creating additional Canva headers and elements led to a continually evolving website that is now referenced in all of our work. The addition of a Google Analytics widget allows us to track the daily demographics of our website readers.

I’d like to claim that as we wrote for these audiences we were consciously following the recommendations of literacy experts such as David Reinking, Deborah Dillon, David O’Brien, and Elizabeth Heilman, who argue that literacy inquiry of the past has been ineffective. Thus, they recommend that inquiry should shift focus to a more practical paradigm that improves human well-being, addresses pressing problems in authentic contexts, and communicates research outcomes with public audiences in language they can understand. Instead, we used Canva and WordPress to help us achieve similar goals somewhat serendipitously as we sought to communicate and connect with our community.

In addition, sharing our work more widely and explaining it simply has, without a doubt, helped us understand our work through the lens of local stakeholders. So, whether using these tech tools to simplify or share project outcomes for academics, students, or teachers, their combined power offers the potential to convey most any message to an audience of choice.

Terry S. Atkinson is an associate professor in the Department of Literacy Studies, English Education, and History Education at East Carolina University in Greenville, NC.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).