The library–media center of old was a silent place where students read, researched, and studied in isolation. However, as students are asked to think more critically, create, and discuss, the library–media center has evolved into a place where collaboration and engaging discussions take place.

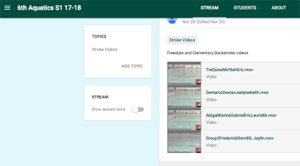

Recently I worked with physical education teacher Colleen Donakowski and her aquatics class to help students analyze their freestyle and elementary backstroke. We started by recording each student swimming two widths of the pool. The first width was freestyle and the second was elementary backstroke. After their swimming demonstrations, I edited the footage so small groups of students could watch and critique their swimming abilities. About four class days later, when the students reported to class, they went to the media center instead of the pool.

When the first group of students arrived, one student asked, “Mrs. Clayton. This is a library, right? Why do we have so many flat screens in here?” I was excited for them to discover why.

The planning stage

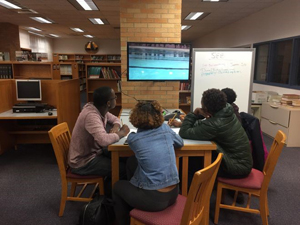

Groups of three to five students were assigned to a collaboration station that included a Chromebook, flat screen monitor, and dry erase board. Within Google Classroom, each group quickly accessed their video.

Groups of three to five students were assigned to a collaboration station that included a Chromebook, flat screen monitor, and dry erase board. Within Google Classroom, each group quickly accessed their video.

Before viewing

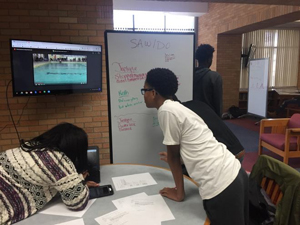

At the dry erase board that was set up at each station, students were asked to write down what they thought their group would see when that person swam their freestyle and elementary backstroke. Each person wrote their own notes on the board. Then they sat down to watch their video.

At the dry erase board that was set up at each station, students were asked to write down what they thought their group would see when that person swam their freestyle and elementary backstroke. Each person wrote their own notes on the board. Then they sat down to watch their video.

During viewing

As each student played their individual video, group members compared the student’s attempt at the stroke to a set of stroke guidelines that had been prepared and distributed for analysis. They also collaborated with each other by providing warm feedback and suggestions for improvement.

As each student played their individual video, group members compared the student’s attempt at the stroke to a set of stroke guidelines that had been prepared and distributed for analysis. They also collaborated with each other by providing warm feedback and suggestions for improvement.

After viewing

Each group member took turns discussing the notes they had taken to help each individual think critically about and reflect on what they saw in the video. Students wrote down what they planned to do to improve their stroke once they were back in the pool.

Each group member took turns discussing the notes they had taken to help each individual think critically about and reflect on what they saw in the video. Students wrote down what they planned to do to improve their stroke once they were back in the pool.

Observations and suggestions

When there is planning time for both the classroom teacher and the instructional technology coach, collaboration stations provide opportunities to facilitate deeper learning for all students. Moreover, keeping group size small opens a gateway into the discussion for even the shyest of students.

A tightly planned lesson helps to keep students on task during this activity. Additionally, give the instructional technology coach time to prepare the media center in advance to ensure that all the equipment is set up, working, and ready before the students arrive.

How can you use collaboration stations?

The ways to use the collaboration stations are limited only by your imagination. Can your students work in collaborative groups to discuss and research current societal issues? To make plans to build something? To conduct research for a project? To work on a math problem? To analyze a piece of student-produced writing? To analyze student performances in broadcasting, instrumental music, and sports? The opportunities are endless.

Kara Clayton is a video production teacher and instructional technology coach at Thurston High School in the South Redford School District in Redford, MI, and offers professional development on the integration of video production in the classroom.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).