Many students struggle with sourcing, specifically, how to use source information to evaluate online sources or how to cite ones’ sources in the essay. Some students may not know how to source while others have knowledge about sourcing, but they don’t typically choose to apply that knowledge in practice This might be because they do not understand the value of sourcing.

When investigating how children respond to information differently from adults and how they select whom to trust, researchers Paul Harris and Kathleen Corriveau found that, even for children, the source of information matters. For example, when two caregivers presented different statements, the children turned to the more familiar caregiver for confirmation. Children seemed to be nonselective in what they learn from others, but not in whom they learn from. This kind of spontaneous attention to sources of information may serve as a starting point for educators when explaining to students why sourcing matters. So, let’s do that!

We will begin by sharing two examples that teachers could use to discuss the value of sourcing with their students. The first example from everyday life takes advantages of students’ spontaneous attention to sources and can also be used with younger students. The second example illustrates how information about the source may affect one's interpretation of a text's reliability. It also shows why one should pay attention to different aspects of the source during online inquiry.

When students have understood the value of source information, they may be better motivated to cite their sources when reporting the results of their online research in a way that serves their readers. To provide informative in-texts citations, students need some guidelines. Our third example introduces two dimensions that students can keep in mind when formulating in-text citations.

Example no. 1: Sourcing in everyday life

Draw students’ attention to the value of citations by showing them a short message without a source (signature) and then, the same message with different signatures, following the stickers below (created with digital Superstickies).

- After showing the first note, without the source, begin the conversation by asking students, “Would you like to know who has written the note? Why?”

- After revealing the three other notes and calling attention to the different signatures (or sources) of each, ask students, “How do you interpret and react to the notes with different sources (signatures)?"

Example no. 2: Sourcing when evaluating the reliability of a website

Discuss the value of sourcing by asking students to evaluate the reliability of a fictitious website after showing them one piece of source information at the time, as listed below.

- How reliable do you find the Web text that concerns health effects of chocolate when you know that:

- An expert working at the health institute has been interviewed for the text?

- The text has been published recently?

- The text has been written by a web designer?

- The text is published in the website of a chocolate manufacturer?

- How did your interpretations on reliability change after each new piece of information about the source?

- Do you think that one piece of information about the source is enough to make a proper conclusion about the reliability of the text? Why do you think so?

Example no. 3: How to cite your Web sources in an essay?

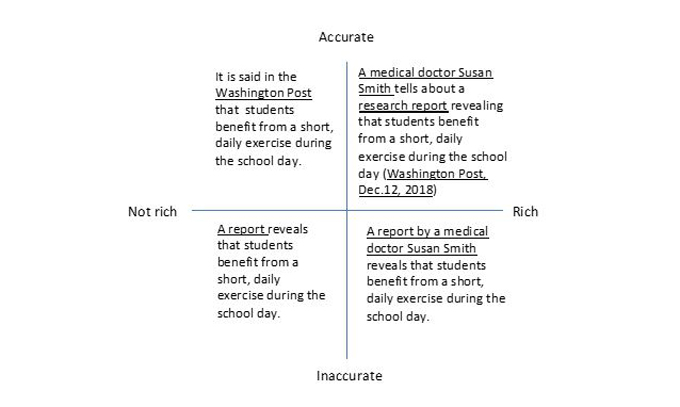

When older students are asked to formulate in-text citations in their essays, it is important that their citations are both accurate and provides rich information about the source. An accurate citation provides precise information about the Web page that students had actually read (e.g., it is published by The Washington Post). A citation that provides rich information includes two or more pieces of information that helps a reader to understand the nature of the source.

These two important dimensions can be introduced to students by using examples from the figure below. In the examples, source information is underlined.

After explaining the dimensions, encourage your students to apply these principles in their essays.

Eva Wennås Brante is a senior lecturer at the University of Malmö, Sweden.

Carita Kiili is a postdoctoral fellows at the Department of Education at the University of Oslo.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).