Many years ago, I sat down with a fourth-grade student to review one of her papers. We discussed the comments and suggestions I had written and established shared goals. At the end of the conference, I asked her if she had any questions, to which she responded, “You tell me what you do, but will I be able to do it?” The content of this blog post reminds me of my former student’s question.

Many years ago, I sat down with a fourth-grade student to review one of her papers. We discussed the comments and suggestions I had written and established shared goals. At the end of the conference, I asked her if she had any questions, to which she responded, “You tell me what you do, but will I be able to do it?” The content of this blog post reminds me of my former student’s question.

Both in research and in practice, “we” (i.e., federal and local policymakers and researchers) “tell” educators, parents, and others about the importance of teaching and learning in the 21st century and about developing our students’ abilities to comprehend, communicate, and evaluate information in digital forms. On the other hand, it appears that what we know about the need to develop students’ 21st-century literacy skills conflicts with the realities of everyday teaching and learning and other literacy-related and educational goals.

Top three requests related to digital literacy

Over the years, I have been involved in school-based professional development, collaborative projects between my university and school districts, and funded projects that have focused on the language and literacy needs of teachers and students across grade-levels and content areas. I have conducted several workshops on digital literacy, disciplinary literacy, and online reading comprehension, among others.

These are the top three requests (related to digital literacy) I hear from teachers:

- Digital content they can incorporate into their curricula for differentiated instruction purposes

- Instructional ideas about how to develop students’ digital literacy without sacrificing content

- Guidance on how to communicate to their principals, and to others who evaluate them, the role of digital literacies in supporting students’ overall literacy, content knowledge, and skills

Digital literacy is more “hot” than “important”

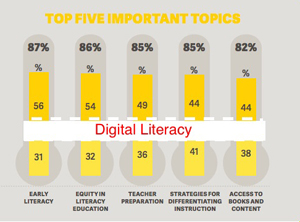

These situated teacher needs support ILA’s 2018 What’s Hot in Literacy survey findings, which rank Digital Literacy No. 1 among all hot topics but No. 13 in terms of importance. Respondents expressed concern that digital literacy is being presented as a quick fix for complex teaching and learning issues and that it is “crowding out a focus on basic foundational literacy skills.”

These situated teacher needs support ILA’s 2018 What’s Hot in Literacy survey findings, which rank Digital Literacy No. 1 among all hot topics but No. 13 in terms of importance. Respondents expressed concern that digital literacy is being presented as a quick fix for complex teaching and learning issues and that it is “crowding out a focus on basic foundational literacy skills.”

Although I both recognize and understand the challenges of adopting a 21st-century instructional and pedagogical digital literacies framework, I also wonder what would happen if digital literacies were conceptualized as a common “thread” that both supports and develops within each one of the top five important literacy topics ranked in the findings: Early Literacy, Equity in Literacy Education, Teacher Preparation, Strategies for Differentiating Instruction, and Access to Books and Content.

Recommendations

The 21st-century literacy skills students need to develop are far greater than the sum of their parts; literacy is given meaning by the cultural discourses, practices, and contexts in which it is surrounded. Young readers need to develop their reading and literacy skills using print and digital texts in ways that are developmentally appropriate. In my view, the reported disconnect between digital literacy’s trendiness and importance also highlights the need for more supports that specialized literacy professionals and digital literacy researchers can provide to teachers and parents about the role of digital literacy during the early literacy, intermediate, and adolescent years.

For example, when I teach my students how to locate, read, comprehend, and evaluate information about the Great Migration movement from the History Channel and how to analyze primary sources from the National Archives, I am accessing content while demonstrating digital literacy knowledge and skills. I spend time over the course of the year modeling, providing feedback, and creating opportunities for my students to collaborate with peers, discuss, and apply what they learn in my classroom in a variety of learning spaces.

I also use a variety of digital and print texts and resources (e.g., The Great Migration: An American Story by Jacob Lawrence (1993); This is the Rope: A Story from the Great Migration by Jacqueline Woodson (2013); and relevant Newsela articles—e.g., “Jim Crow and The Great Migration” and “Songs of African-American Migration were Influential Across the Land.” Furthermore, I differentiate my instruction, the texts, and the supports I provide to help all students construct meaning.

Digital literacy is neither a quick remedy for the complex demands of literacy teaching and learning nor a substitute for the expert classroom teacher. In closing, I choose to view the results of ILA’s 2018 What’s Hot in Literacy Report as a call for new, teacher-centered, collaborative, relevant, and strategic discussions among specialized literacy professionals, K–12 educators, researchers, and teacher educators.

Vicky Zygouris-Coe is a professor of reading education at the University of Central Florida.

Vicky Zygouris-Coe is a professor of reading education at the University of Central Florida.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).