Recently I was given an opportunity to interview teachers in Germany about their methods for teaching students to conduct online inquiry. Although I came away from these discussions with a variety of insights, the acknowledgment from a majority of the teachers that students need more preparation in critically evaluating online information resonated with me. I’ve heard similar comments from teachers in the United States and South Africa and read various research reports confirming this need.

Recently I was given an opportunity to interview teachers in Germany about their methods for teaching students to conduct online inquiry. Although I came away from these discussions with a variety of insights, the acknowledgment from a majority of the teachers that students need more preparation in critically evaluating online information resonated with me. I’ve heard similar comments from teachers in the United States and South Africa and read various research reports confirming this need.

Cited as one of the five primary processes within online research and comprehension, the evaluation of online information is unique to the digital age. With the click of a mouse, information is now available worldwide, regardless of its credibility or accuracy. Perhaps as a result of this situation, curricular frameworks in Australia, Manitoba, Canada, and the United States require the development of skills in evaluating information found online. Teachers, however, appear to lack specific processes to teach students how to consistently engage in strategies to verify and assess trustworthiness and reliability. Conversations have revealed a tendency to tell students that they should not use Wikipedia as a source. Yet there is much more to this process. Just as students need strategy instruction to be successful within “traditional” reading activities, they also benefit from explicit instruction in how and when to evaluate information found online.

Given the need for instruction in this area, there are several resources I think will be helpful for developing plans to teach this critical skill. First, I recommend an article by Shenglan Zhang, Nell Duke, and Laura Jiménez that describes the WWWDOT framework (Who wrote this and what credentials do they have? Why was it written? When was it written and updated? Does this help meet my needs? Organization of website. To-do list for the future.), which teaches students to direct their attention to six aforementioned dimensions of websites. In collecting and assessing this information, students render a decision on the trustworthiness of the site. What is helpful about the article is the description of one teacher’s process of teaching the framework across four lessons.

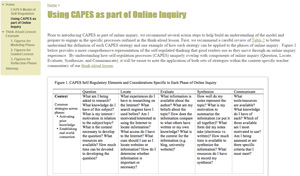

Julie Coiro and I also wrote an E-ssentials piece on how to use CAPES (Context, Actions, Products, Evaluation, and Standards) self-regulatory framework. The framework requires students to ask a series of questions, plan actions based on the questions, then evaluate the website on the basis of specific criteria (i.e., standardsof reliability)to determine whether it’s a trustworthy source of information. The article contains a shortened example of a think-aloud that can be used to teach the process of evaluation, and a companion site demonstrates the process in greater depth.

Another useful set of thinking prompts and lesson ideas can be found at Julie Coiro’s post on Edutopia. From here, you can also read preliminary results of a study conducted among 770 seventh graders asked to make judgments about a website author’s level of expertise, his or her point of view, and the overall trustworthiness of the information provided. Finally, there are several resources found at ReadWriteThink.org, including a strategy guide and a lesson plan, which both inform and help in lesson development. The common characteristic across the resources is that students are being taught to stop, plan, and reflect about websites and authors, actions they don’t normally take when seeking information.

As a final thought, let me share a comment from one of the German teachers in reference to Wikipedia. He said we forget some Wikipedia entries, such as one about The Beatles, have been edited and vetted by many experts on the band, thus providing factual information. So, instead of telling students they cannot use the website, he allows them to visit it first (which seems to be their natural inclination anyway) and asks them to consider the information on the site as well as the references. Rather than avoid sites that might be questionable, his message was that if we can teach students to effectively implement strategies for thinking about and examining websites and information, they can still effectively use the resources they are most comfortable with. In turn, we can be comfortable knowing that we have prepared them to be systematic, analytic, and critical, as they search for information in the digital age.

Michael Putnam is an associate professor and interim chair for the Department of Reading and Elementary Education at University of North Carolina at Charlotte. This article is part of a series from the International Reading Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).

Michael Putnam is an associate professor and interim chair for the Department of Reading and Elementary Education at University of North Carolina at Charlotte. This article is part of a series from the International Reading Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).