3D printing—an emerging technology that facilitates the creation of objects through material design—is a powerful educational tool. Research has documented the technological affordances of 3D printing as an innovative learning tool across disciplines such as secondary history, anatomy, chemistry, and technology education. Despite these STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) perspectives, 3D printing is a lesser known technology in teacher education classrooms and, more broadly in English language arts classrooms. I work with prospective teachers in an undergraduate education program, and one of the classes I teach is titled “Teaching Social Studies and the Arts.” Through experimentation, I've discovered ways to mobilize 3D printing as both an educational technology and an artistic medium for developing my undergraduate students’ response to children’s and young adult literature.

Fabricating a response: Explore, engage, and evaluate

The “Fabricating Response…” assignment was designed to demonstrate the connection between technology, literacy, visual arts, and social studies. The 3D printing project engaged prospective teachers in a collaborative, semi-guided inquiry activity. As part of their inquiry, they were asked to design an “artifact” that signaled their response to Francisco Jimenez’s The Circuit: Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child (University of New Mexico), one of the central young adult texts in the course. We centered our literary inquiry on the topic of immigration, and used 3D modeling and printing technologies to discuss the politics of design. In essence, we explored how responding with the visual arts could enhance, affect, and/or reject student’s responses to a text.

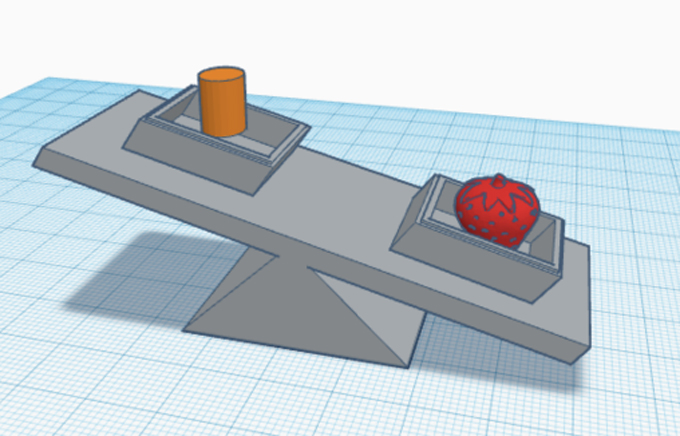

Spanning three class meetings, the project followed a three-phase model of explore, engage, and evaluate. During the explore session, prospective teachers became familiar with 3D printing technologies and software such as Tinkercad (see figure above). In this phase, our conversations focused primarily on integrating children’s and young adult literature in the social studies curriculum. After discussing central themes of The Circuit, we examined what it may mean to crystalize our understanding of these themes through materials. Prospective teachers used an array of materials (e.g., rocks, tempera paints, pipe cleaners, etc.) to respond (see figure below). This introductory class session was critical to building an understanding of how elements of design (i.e, color and texture) led to both literal and metaphorical responses to The Circuit’s plot.

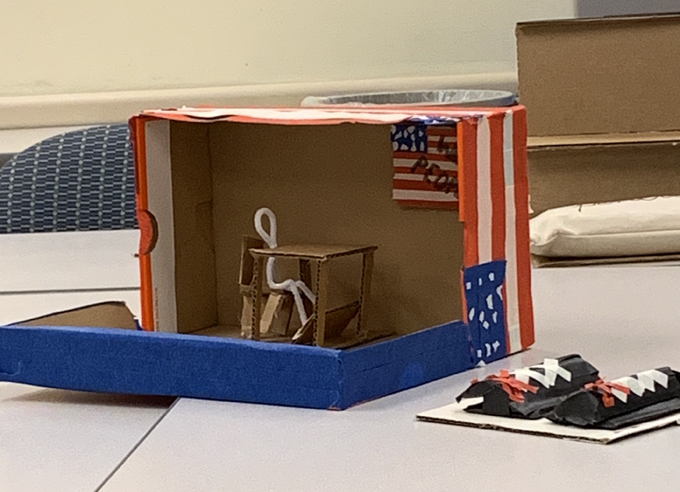

During the engage phase, prospective teachers worked in grade-level teams to both discuss the focal text and prototype their design using cardboard (see below). Our discussion in this session focused on understanding the politics of response as design. With a goal of having three prototypes to share during the last phase, prospective educators brainstormed numerous possibilities. As expected, students were less familiar with the technical elements of 3D printing. As a result, they were drawn toward third-party sites like Thingiverse to remix and remediate user-produced designs.

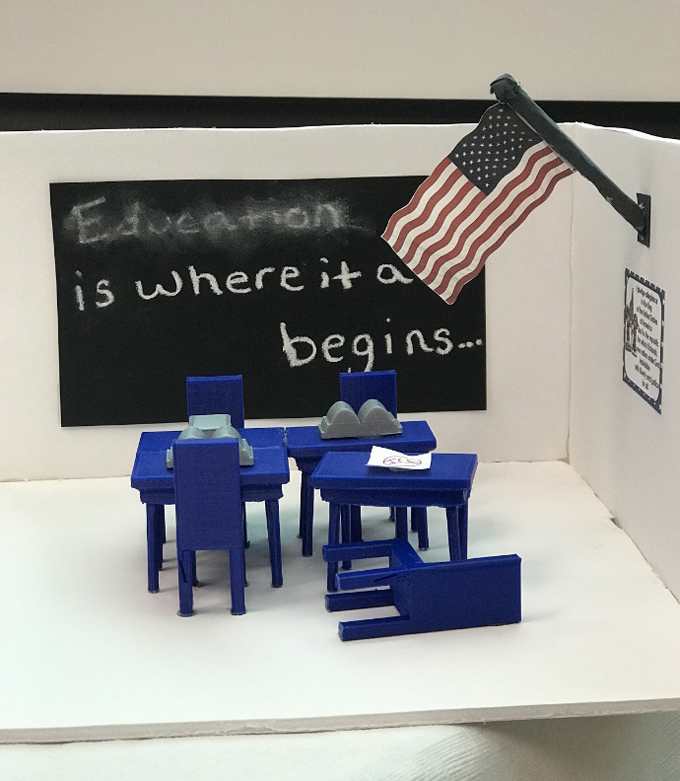

In the third and final phase, students staged and evaluated their group’s 3D artifacts. Using a variety of critique protocols and strategies (e.g., Visual Thinking Strategies), we collaboratively talked across the affordances, constraints, and tensions of fabricating response. Working with mixed media, prospective teachers were asked about their responses as they detailed the artifact’s purpose and possible reception. After this final in-class session, students returned to their prototype designs and revised them for the final time. Afterward, students submitted the final TinkerCad file and used the 3D printers to print their designs in class.

So, what? Why 3D print?

As we discovered, most students worked toward the prepared goals of multimodal design. In other words, designing the 3D artifact merely encouraged students to reproduce the knowledge they received during the instructional activity. TinkerCad was a means to an end, rather than an iterative tool to disrupt or otherwise challenge traditional ways of thinking about design and literary response.

Conceptually, however, fabricating response illuminated the material conditions of ideology and the politics of arts-integrated response. In other words, what students designed signaled their attitudes concerning the recent rhetoric surrounding the Mexico–U.S. border wall and beliefs about immigration. Prospective teachers used the available tools of design to construct a 3D artifact that conceptually detailed personal responsibility (e.g., an empty classroom with a single chair knocked down) over a pertinent topic and theme (e.g., immigration and the inequitable education for migrant youth) in The Circuit.

Teachers were also concerned by the limitations of 3D printing and yearned to use other aesthetic materials and media to design meaning. As Colleen, a prospective teacher, described, “I couldn’t just design something on TinkerCad and be OK with the printing. I felt like I needed to make something more, something else.” In sum, prospective teachers felt as if they had to use media outside of 3D printing in order to illustrate their personal conviction of a political topic (see figure above).

By encouraging invention and fostering creative thinking, 3D printing served as an invitation to arts-based production and literary response. I encourage you to explore the possibilities of 3D printing in your own learning space to see firsthand how the practice can help to promote design-based learning, creativity, and critical thinking.

Jon M. Wargo is an assistant professor of literacy in the Lynch School of Education and Human Development, where he teaches undergraduate and graduate level courses in digital literacies, qualitative research methods, and arts-based inquiry. Follow Jon on Twitter @wargojon.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).