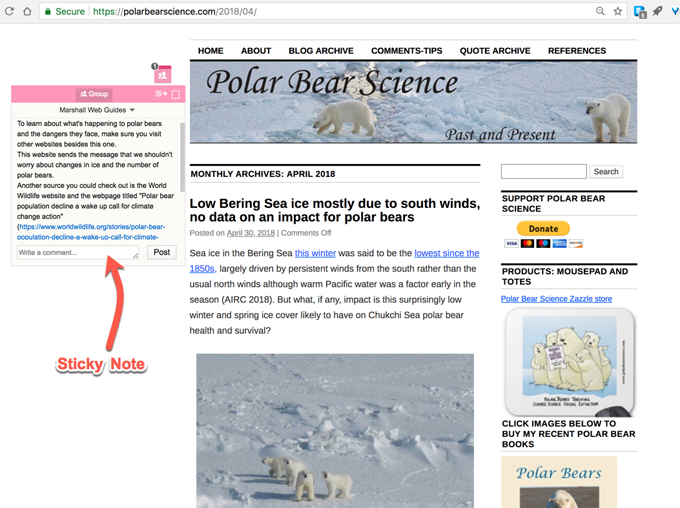

“Okay Web Guides, what type of ‘reader alert’ or ‘navigation help’ sticky note should we put on this website to help other sixth graders? What should it say?”

“Okay Web Guides, what type of ‘reader alert’ or ‘navigation help’ sticky note should we put on this website to help other sixth graders? What should it say?”

One by one, the sixth graders chimed in.

“The alert could say, ‘Make sure you also visit other websites about global warming,’” one student suggested.

“We could include links to other websites,’” said another.

The brainstorming discussion continued for several more minutes. Then it was time to type the sticky note and place it on the target website. Although the students were familiar with this step, the moment of actually placing the sticky note where it would be seen by other sixth graders generated lively discussion and excitement.

“Put it here in the white space where it’ll be easier to see!”

“Let’s check that the links work.”

As we concluded the activity for the day, I asked the group, “How many of you are ready to be a Web Guide on your own tomorrow? How many of you are ready to train someone else to be a Web Guide?”

In this small group of five summer campers, everyone’s hand shot up.

The importance of roles and identities for learning

Literacy growth is about acquiring new skills and new knowledge, but it’s also about growing into new roles. These roles are an important part of literacy development because they connect the skills and knowledge our students acquire in school—about vocabulary, text structure, reading comprehension strategies, and so much more—to identities and purposes that have meaning and value beyond just “doing school.”

Consider, for example, a class of sixth graders reading expository informational texts to learn about pond and lake ecosystems. If these students have no purpose for learning other than doing well on a future test and no role to play other than that of diligent student, the available research suggests that many may come away without deep understanding of ecosystems and without much improvement in their ability to read and write expository informational texts.

By contrast, if learning about pond and lake ecosystems is connected to an authentic task (such as producing an informational brochure for visitors at a nearby nature center) and inhabiting a meaningful new role (such as environmental scientist or freelance designer of educational materials), more students are likely to feel engaged and motivated.

As they grapple with new technical terms and get better at parsing dense informational texts, they aren’t just accumulating knowledge and skills to get a good grade. These students are inhabiting a new role that connects them to an audience and adds value to the world—making contributions about which they can feel proud.

Learning to be a safe and critical web user

This issue of roles and purposes is on my mind this summer in relation to the internet safety concerns Michelle Hagerman addressed in her recent blog post as well as the challenge of helping all students become critical seekers and users of information on the web.

Working with students in grades 4–12 as well as with preservice teachers, I’ve observed that, while the self-protective purpose of staying safe on the internet is generally acknowledged, learning strategies for staying safe and becoming a critical reader and researcher on the internet isn’t usually connected to any new role or identity students can grow into and feel proud of.

As a result, I’ve seen students leave class having learned a thing or two about noticing a website’s domain name (e.g., .com, .net, .org), checking out a website’s “About” page, and not divulging one’s name or address online. But I often have not felt confident that this new knowledge is going to stick and be applied in the future.

Growing guides and lifeguards of the internet

Alongside K–12 colleagues, I’m working this summer to develop curriculum that puts roles center-stage. Our idea is to have students train to become “guides” and “lifeguards” of the internet. They will learn to use free web tools such as Diigo and InsertLearning to provide peers and younger students at their school with tips, alerts, helpful resources, and encouragement to safely and critically navigate designated websites.

Alongside K–12 colleagues, I’m working this summer to develop curriculum that puts roles center-stage. Our idea is to have students train to become “guides” and “lifeguards” of the internet. They will learn to use free web tools such as Diigo and InsertLearning to provide peers and younger students at their school with tips, alerts, helpful resources, and encouragement to safely and critically navigate designated websites.

The appeal of these free web tools is that the annotations they create appear to the user to reside on the web page where they are posted. When other students visit an annotated web page, as long as they have logged into Diigo or InsertLearning and are members of a designated group (Diigo) or class (Insertlearning), they will encounter sticky notes and other annotations as though they were part of the web page (as illustrated above).

Our initial trials with this approach look promising. For students, the work is about more than just gaining more knowledge and skills for self-protection and individual success on the web; it’s about stepping into a new role in a community of learners, looking out for others, and developing knowledge and skills that feel relevant and valuable.

Our initial trials with this approach look promising. For students, the work is about more than just gaining more knowledge and skills for self-protection and individual success on the web; it’s about stepping into a new role in a community of learners, looking out for others, and developing knowledge and skills that feel relevant and valuable.

What innovative ideas have you tried out to connect your students to meaningful roles and purposes to deepen their literacy learning?

Paul Morsink is an assistant professor in Reading and Language Arts at Oakland University in Michigan.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).