It’s Banned Books Week, and all across the United States, public libraries feature displays encouraging patrons to read banned books. Somewhere, someone will pick up a book from one of those displays and say, “Whoa. This has been banned?”

It’s Banned Books Week, and all across the United States, public libraries feature displays encouraging patrons to read banned books. Somewhere, someone will pick up a book from one of those displays and say, “Whoa. This has been banned?”

Book banning is a loaded term that implies totalitarianism and conjures up images of bonfires. Library patrons sometimes look disappointed when they learn that the book they are holding in their hands has not been banned outright, only challenged.

Banning and challenges are often conflated by librarians and other literacy advocates including the American Library Association (ALA), which annually publishes a list of the most frequently “Banned and Challenged Books.” ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom explains the difference: “A challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group. A banning is the removal of those materials.”

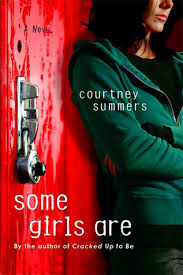

Here in Charleston, SC, the book Some Girls Are by Courtney Summers was challenged recently when a parent declared the book, which deals with difficult issues like sexual assault and bullying, “trash,” and requested its removal from the summer reading list at West Ashley High School.

The principal of West Ashley High culled the book from the reading list before a committee could review the parent’s complaint. (It was replaced by Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, which, ironically, appears on ALA’s list of Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books, 2000-2009). The parent also requested the book be removed from the school library, but this action was not taken. The school district has since formed a Literacy Advisory Council to address this and other curriculum challenges.

News of a challenge spreads quickly in the book-loving world, and within days I was contacted by famed book blogger and teen advocate Kelly Jensen, who asked if I was willing to try something. If she requested people send her copies of Some Girls Are, would I find a way to get them into the hands of any students who wanted them? I was all in.

Not only do I believe in standing up for the freedom to read in general, I have strong feelings about this book in particular. Over the years, I’ve recommended it frequently to teen readers, many of whom have returned to say how deeply it affected them. Some Girls Are has sparked real, honest conversations with teen girls about the issues they face. It’s a powerful and important book, and dismissing it as “trash” is insulting not only to its author but also to all the young people who have found truth and solace in its pages.

Kelly wrote about the situation on her blog, Stacked Books, and issued a challenge of her own: “Let’s do something together with our collective reader, intellectual freedom-loving power, shall we? Can we get this book into the hands of kids of West Ashley who want it?”

The next day, she e-mailed me: “Be prepared. This is going to be much, much bigger than I anticipated.”

A couple of weeks later, boxes of books started arriving at my office door. They are still trickling in. So far, more than 1,000 copies of Some Girls Are have been donated, and I can barely find my desk beneath all those boxes.

Here at the Main Library Teen Lounge, I cleared out an entire bookcase and filled it with donated copies. Library branches serving the West Ashley community also set up displays. Local news picked up the story, and other branches of the Charleston County Public Library offered to help with distribution after their visitors asked about the book.

The best part of this project has been the discussions library staff have had with teens and tweens as a result. They want to know, “What’s the deal with this book? Why do you have so many copies?” They listen thoughtfully as we explain, and then say things like, “Wait, they took it off the list just because one person didn't like it? That's like if I said that just because I didn't like Divergent then no one should read it. That's just wrong."

Teens take home a copy and come back to say, “I can’t believe they took it off the list. I mean, it has some bad words in it—a lot of them, actually—but like, the things it talks about are really important. Cause stuff like that happens in real life. It's sad."

When I tell these teens that total strangers from all over sent these books because they care so much about them, their lives, and their ability to choose for themselves what they do or don’t read, their jaws drop and eyes widen in amazement.

Some have asked, “What’s the big deal? The book wasn’t banned. It’s still in the school library.” But here’s the thing: It’s crucial that we stand up for the freedom to read, speak out when challenges occur, and stand up to censorship attempts. Left unchecked, these elements easily can start a slippery slope that results in actual bans and even book burnings.

Andria Amaral was the first Young Adult Librarian in the state of South Carolina, joining the staff of the Charleston County Public Library in 1997. She has spent 18 years planning and developing public library collections and services for students in grades 6–12, including after-school activities, summer reading contests, and innovative outreach programs targeting at-risk and incarcerated teens. Andria has provided professional development workshops at state and national library conferences and has been a guest lecturer to MLIS students at the University of South Carolina and YA Literature students at the College of Charleston. She also serves on the YALLFest Board of Directors. She lives in Charleston, SC, with her husband and four dogs.

Andria Amaral was the first Young Adult Librarian in the state of South Carolina, joining the staff of the Charleston County Public Library in 1997. She has spent 18 years planning and developing public library collections and services for students in grades 6–12, including after-school activities, summer reading contests, and innovative outreach programs targeting at-risk and incarcerated teens. Andria has provided professional development workshops at state and national library conferences and has been a guest lecturer to MLIS students at the University of South Carolina and YA Literature students at the College of Charleston. She also serves on the YALLFest Board of Directors. She lives in Charleston, SC, with her husband and four dogs.