In October, our article, Science Writer and Universal Design for Learning, Stacey Reed, a seventh grade life science teacher in Wayland, Massachusetts, presented ideas for how to use Science Writer, a free interactive web-based instructional tool to support students’ writing scientific reports. Based on the framework of Universal Design for Learning, Science Writer provides students with many choices and levels of support for learning. Student engagement is increased by the fact that each student makes decisions about how much or how little support they require while they develop the report. Stacey also shared a chart that she developed highlighting the process she uses to engage students in designing good experiments, asking good questions and communicating their thoughts in a scientific manner. In this article, Stacey will share additional ideas she uses to support student engagement with the scientific process.

The culminating assignment of a course I took a couple of years ago was the seemingly mundane assignment of giving a presentation to the class on a topic with a partner. One twist, however, was that I had never met any of the classmates I had been working with for the past several weeks. There was also the small detail of my partner living in Singapore with a 12-hour time difference. My partner and I had to work out how to work asynchronously online to create a product. In the human body unit, I strove to provide my students with a similar experience in order to prepare them for the asynchronous collaborative environments of their future study and work.

Before researching, we built some background knowledge in a flipped classroom. Students accessed information via my website and completed Google forms before conducting experiments during class. The information included videos from TedEd, BrainPop, and news clips, as well as articles. Many students found the text-to-speech feature (found in many browsers as Edit--->Speech) particularly useful while developing technical vocabulary. Students are intrinsically interested and have many specific questions during this human anatomy unit of my life science classroom. Conducting a research project is a great way to channel these questions and, in the process, tap in to various CCSS standards while accomplishing major NGSS content standards. This project was heavily influenced by the NGSS cross-cutting concept of structure and function, and the body system content standard of MS-LS1-3. Students also evaluated resources and collaboratively published a research project, utilizing standards from CCSS, specifically ELA.W.7.6-8.

Reed's students present their posters

Reed's students present their posters

about life science

In order to accomplish these goals, students from different sections of my science classes then chose health issue topics and were matched, with each topic being unique. Many were matched with unfamiliar classmates. A few students remarked that being able to work asynchronously instead of sitting next to their partner allowed them to feel less stressed and work at their own pace. About a third of students worked only face-to-face with their partner, whereas the majority of students used at least one asynchronous communication tool.

Students used a common Google Doc of research cards from my copied template to record their research. Each card had space to record the keywords used, the relevant subtopic, the direct quote, a paraphrase, and bibliographic information. Having both the direct quote and the paraphrase on the same page allowed me to evaluate their understanding and, if needed, direct towards more accessible reading. Google Advanced Search and many library catalogs allow students to search for information at various levels. Students devised many different strategies to organize the information on the shared document, many using color-coding to signify subtopics and card ownership.

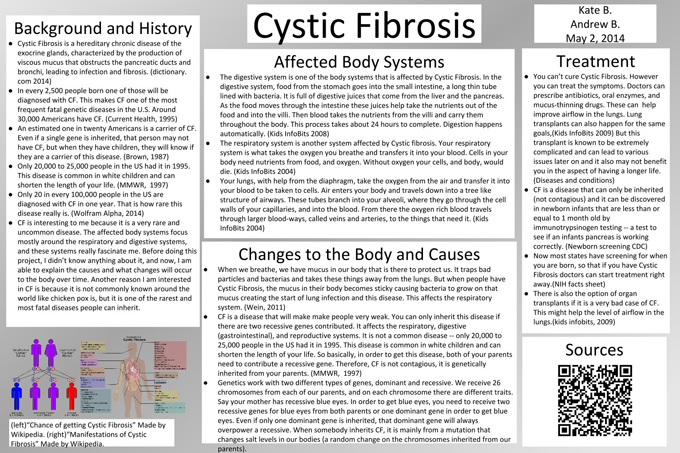

Students then took their information and created a research poster in Google Slides, copied from a template. The template was modeled from research posters I had created in college and graduate school to explain my research during poster sessions. Students could choose to use a guided template or work from a blank version. When the information was complete and all of the sources were cited, students submitted their work to a shared Google Drive folder. I then printed and hung the 24”x36” posters, and students had their own poster session. Students had prepared answers for at least five mandatory questions that faculty would assess, but also for the back and forth of a conversation. With technical vocabulary like “anterior tibial tubercle” and “leukocytes” used in conversation during the session, students demonstrated how expert in their fields they had become.

Sample Google Slides Projects