by Paul Morsink

by Paul Morsink

At what point does a new technology become so ubiquitous, so familiar and taken-for-granted, that assessing students’ performance in the absence of that technology is seen by researchers, educators, and students themselves as artificial or unfair?

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) offers different answers, depending on whether we’re talking about reading or writing.

In 2010, the authors of the NAEP Writing Assessment clearly felt a tipping point had been reached. They voted to deliver the 2011 Writing Assessment in a fully digital format and, for the first time, to give students the option of accessing a variety of digital writing supports (e.g., copy/paste, text-to-speech, spell-check, thesaurus).

The rationale for this move (laid out in the 2011 NAEP Writing Framework document) makes for interesting reading. After describing at some length the reality that new “communications technologies [have] changed the way people write and the kinds of writing they do,” the authors asserted the following:

[E]liminating access to common word processing tools on the computer would create a highly artificial platform for composing, since a writer normally has access to and uses at least some common tools when composing on a computer. The purpose of assessing writing produced on the computer comes into question when access to such common features of word processing software is eliminated. (p. 9)

The authors acknowledged that some students “who are not comfortable with electronic composition” may be disadvantaged by the digital format. At the same time, they pointed out that “a paper and pencil assessment would create similar issues of bias for students who commonly use computers to write” (p. 8). At the end of the day, then, they decided to go digital and allow digital writing supports because the “NAEP Writing Assessment [should reflect] the way [most of] today’s students compose—and are expected to compose—particularly as they move into various postsecondary settings” (p. vi).

The authors acknowledged that some students “who are not comfortable with electronic composition” may be disadvantaged by the digital format. At the same time, they pointed out that “a paper and pencil assessment would create similar issues of bias for students who commonly use computers to write” (p. 8). At the end of the day, then, they decided to go digital and allow digital writing supports because the “NAEP Writing Assessment [should reflect] the way [most of] today’s students compose—and are expected to compose—particularly as they move into various postsecondary settings” (p. vi).

So much for the design of the 2011 NAEP Writing Assessment. (See Dana Grisham and Jill Castek’s October blogpost for discussion of the 2011 Writing Assessment results—in particular the finding that students who used digital tools scored, on average, higher than students who did not use them.)

By contrast, the authors of the NAEP Reading Assessment see the world differently. In the 88-page Reading Framework document they do not devote a single sentence to acknowledging the fact that in U.S. classrooms, and especially outside school, K-12 students starting in Kindergarten are today spending more and more time reading on screens, in an expanding array of genres and formats, for traditional and new tasks and purposes (e.g., studying for an upcoming test as well as exploring a friend’s social media platform profile), and with access to a variety of digital reading supports (text-to-speech, online dictionaries, etc.) (e.g., Barone, 2012; Beach, 2012; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010; Lenhart, 2012; Rainie et al., 2012).

Indeed, the Reading Framework document uses the word computer only once, simply stating that, “it is difficult to include [computer-based electronic texts] in ways that reflect how students actually read them in and out of school” (p. 6). (The paragraph does not elaborate on the precise nature of the difficulty.)

For these authors, apparently, the tipping point has not yet been reached. For now, in their view, a paper and pencil assessment of “what students know and can do” is still fair, accurate, and valid. Eliminating the tools that readers normally have access to and use at least some of the time when reading on a computer, tablet, or mobile device does not pose a problem.

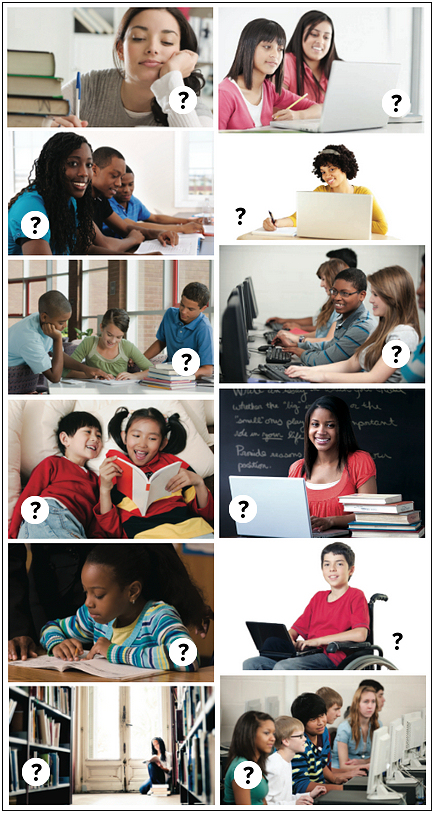

Figure 1. Two contrasting visions of 21st century literacy. Half of these photographs are from the NAEP Writing Report; the other half are from the Reading Report. Can you guess which are which? (Move your cursor over the image to see answers.)

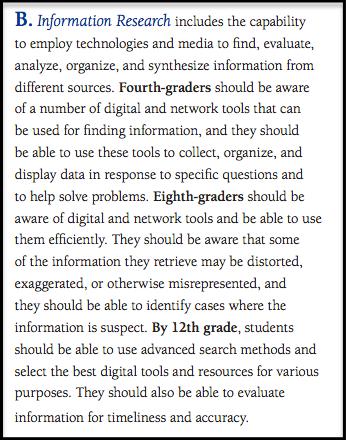

As of next year, however, the Writing Assessment and Reading Assessment will no longer be the only NAEP literacy games in town. NAEP is currently developing a new assessment, the Technology and Engineering Literacy Assessment, to be inaugurated in 2014. Among other things, it will contain questions and performance items pertaining to Information and Communication Technology (ICT). Students will be assessed for their ability “to employ technologies and media to find, evaluate, analyze, organize, and synthesize information from different sources” (p. 8).

In many ways, this new NAEP assessment looks like what could be the future of the Reading Assessment—a future that the authors of the Reading Assessment have so far refused or ignored. Consequently, it appears that—for a time, at least—we may have two different sets of NAEP data to turn to when we want to know how well U.S. students are reading. The NAEP Reading Assessment will tell us about students’ levels of proficiency with traditional print literacy. The NAEP Technology and Engineering Literacy Assessment will tell us about their proficiency with the new literacies of ICT-enabled reading and learning. And this may be a very positive development. If nothing else, it may deepen our understanding of the idea that, today more than ever, reading and writing are non-unitary constructs (Duke, 2005).

Figure 2. Area 3 (“Information and Communication Technology”) of the NAEP Technology and Engineering Literacy Assessment contains five “sub-areas” in which students are assessed. Area B covers “information research.” Source: 2014 Abridged Technology and Engineering Literacy Framework.

References

Barone, D. (2012). Exploring home and school involvement of young children with Web 2.0 and social media. Research in the Schools, 19(1), 1-11.

Beach, R. (2012). Uses of digital tools and literacies in the English Language Arts classroom. Research in the Schools, 19(1), 45-59.

Duke, N. K. (2005). Comprehension of what for what: Comprehension as a nonunitary construct. In S. G. Paris & S. A. Stahl (Eds.), Children's reading comprehension and assessment (pp. 93-104). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2010). Generation M: Media in the lives of 8-to 18-year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/entmedia012010nr.cfm

Lenhart, A. (2012). Teens, smartphones & texting. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones.aspx

National Assessment Governing Board. (2010). Reading framework for the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress. Washington, DC: National Assessment Governing Board.

National Assessment Governing Board. (2010). Writing framework for the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress. Washington, DC: National Assessment Governing Board.

Rainie, L., Zickuhr, K., Purcell, K., Madden, M., & Brenner, J. (2012). The rise of e-reading. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & Family Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org

Paul Morsink is a doctoral student in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology at Michigan State University, morsinkp@msu.edu.

This article is part of a series from the International Reading Association Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).