This is the final installment of a five-part series on cultivating gender-inclusive classrooms. It was written as a complement to “The Power to Include: A Starting Place for Creating Gender-Inclusive Literacy Classrooms,” an article that appears in the July/August issue of Literacy Today, ILA’s member magazine.

Integrating gender nonconforming people into the curriculum can happen across disciplines, but a solid start is to teach with picture books that feature LGBTQ protagonists. For example, the book I Am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings (Dial) offers opportunities to engage in dialogue around challenging the gender binary, and Jazz, a transgender child, is a strong role model for students.

It’s also important to integrate the histories, narratives, and contributions of transgender, genderqueer, and gender nonconforming scientists and mathematicians (such as Joan Roughgarden, Angela Clayton, or Julia Serano), artists (such as ballerina Jin Xing or composer Wendy Carlos), or authors (such as Jazz Jennings or Janet Mock). Equally important is engaging in frequent dialogues about who is left out or misrepresented in literature and picture books. For example, asking students who’s not included, why they think this happens, and who they can include and how not only builds critical thinking skills and empathy, but also sends positive messages about equity and inclusion.

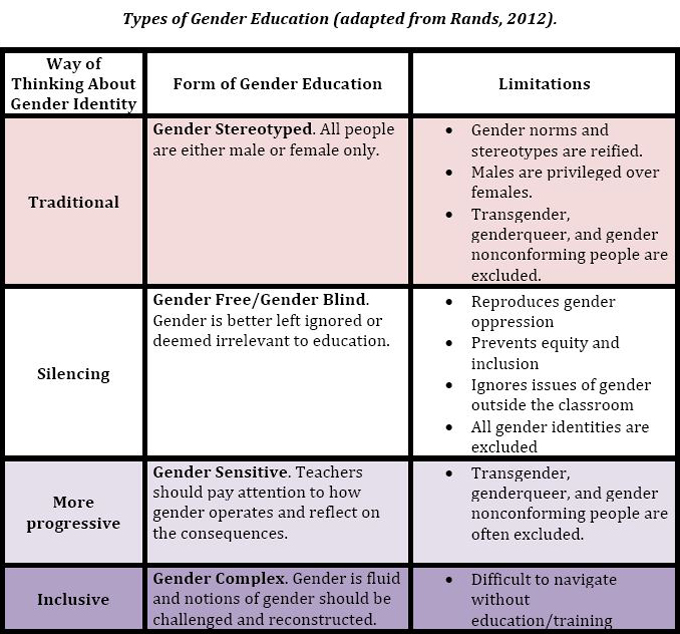

Another part of creating gender-inclusive and equitable literacy curricula means shifting the ways we provide and subscribe to gender education. Scholar Kathleen Rands urges that “educators must take into consideration the existence and needs of transgender, [genderqueer, and gender nonconforming] people, and teach gender in a more complex way” through a “gender complex education.” Teaching the binary of “boy” and “girl” offers an easy interpretation of gender, but it excludes, oppresses, and marginalizes those with different identities. A gender-complex education, on the other hand, although initially more challenging to conceptualize, creates more inclusive, valuing, encouraging situations for the long term.

A gender-complex education recognizes multiple forms of gender identities and challenges traditional thinking around gender. It calls educators to four actions:

Acknowledge gender as fluid.

- Identify gender category oppression, where male is privileged over female.

- Recognize transgender category oppression, where the same woman oppressed by men and male privilege is privileged over a transgender woman because she conforms to gender category norms.

- Challenge gender and transgender category oppression.

Educators must also demonstrate these in the classroom. Teach your students to enact these and interrogate the places where the social construction of gender is influenced by and influences our understanding of gender.

When we start thinking and having conversations with our students about gender in this way, we can start to think about what an integrated complex gender curriculum can look like. The table below shows the different ways of thinking about gender identity. Where do you fall in this chart? What are some moves you can make to think about gender in a more inclusive way?

Dana Stachowiak is an assistant professor of curriculum and instruction in the Watson College of Education at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, where she coordinates the Curriculum Studies for Equity in Education master’s program. Dana is also a literacy consultant with The Educator Collaborative and worked as a curriculum specialist and teacher for a decade in North Carolina. Dana’s primary areas of specialization and research include social justice education, equity literacy, literacy curriculum development, cultural foundations of education, qualitative research methods, and gender studies. Pronouns: She, her, hers. Twitter handle: @DrStachowiak.