Eugene Yelchin does his research before he goes into a school. What are the students learning about? What do they need? Where will he make his presentation? Then he tailors his school visit to each appearance. He may embrace individuality and personalization as a former citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. He escaped the oppressive regime to come to the United States in 1983 at age 27 and began his publishing career in 2007. He is both a writer and an illustrator and eagerly takes his work directly to classrooms around the country.

Eugene Yelchin does his research before he goes into a school. What are the students learning about? What do they need? Where will he make his presentation? Then he tailors his school visit to each appearance. He may embrace individuality and personalization as a former citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. He escaped the oppressive regime to come to the United States in 1983 at age 27 and began his publishing career in 2007. He is both a writer and an illustrator and eagerly takes his work directly to classrooms around the country.

You’re an award-winning author AND illustrator. You know you can do it all. What do you enjoy about collaborating with other authors?

I can’t do it all. Nobody can. In truth, most of the authors and the illustrators arrive at their unique personal style by turning their weaknesses into strengths. Virtuosity, being extremely good at something, could be dangerous for creativity. So is too much confidence. For the most part, art is born out of doubt. As a result, illustrating other authors’ work is a relief from that nagging, all-consuming presence of doubt I feel when I work on my own material. Additionally, there’s a certain distance from someone else’s manuscript, an emotional detachment. It allows me to see clearly whether the idea for the story was fully delivered through its execution by the author. If I had written the manuscript myself, my vision would not be as clear.

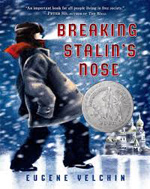

Breaking Stalin’s Nose was a personal story. How does your experience inform all of your work?

I would argue that every artist’s work mirrors his or her biography. We write what we know. Not factually, of course, but emotionally. If you were a theater director you would never ask an actor to express an emotion that you had never experienced. The same is with writing. You can’t ask a reader to have a feeling that you have never felt. Lev Tolstoy wrote a whole book about it called What Is Art? By his definition, art is truly art only when a feeling that the author once felt is expressed in the writing in such a way that when a reader reads that writing, he or she feels the same feeling.

Who or what encouraged you to take chances, to move to the United States, to pursue a life in literature?

Necessity. Living in the USSR was not only dangerous, but also morally corrupt. I left Russia because it was safer to embrace the unknown than to stay in a totalitarian country. While living in the USSR, I had to construct an intricate mechanism of emotional and psychological defenses in order to survive. In the U.S., I realized (eventually realized) that that mechanism of defenses was preventing me from embracing my newfound freedom. As a result, I had to work through my past emotional experiences to rid myself of the hold they still had on me. Breaking Stalin’s Nose was the result of that work.

Necessity. Living in the USSR was not only dangerous, but also morally corrupt. I left Russia because it was safer to embrace the unknown than to stay in a totalitarian country. While living in the USSR, I had to construct an intricate mechanism of emotional and psychological defenses in order to survive. In the U.S., I realized (eventually realized) that that mechanism of defenses was preventing me from embracing my newfound freedom. As a result, I had to work through my past emotional experiences to rid myself of the hold they still had on me. Breaking Stalin’s Nose was the result of that work.

How do you collaborate with teachers in the classroom?

Before I visit a school, I usually speak with the teacher or the principal. I want to know what grades I will be working with. Will we be in a classroom, a library, or at a general school assembly? What are their students studying now? What are they reading? And most important, what do the kids of this particular school need to learn from my visit? Most of the time, I am asked to visit because the students are reading (or being read to) my middle grade books Breaking Stalin’s Nose and Arcady’s Goal. They are curious about the USSR, Communism, and an idea of a dictatorship in general. Because I’ve lived through that period in history, I’m able to make abstract concepts tangible and personal for them. Often, we end up talking about writing—how the students could use their own life experiences as a material for constructing a narrative. Obviously, when I visit with the little kids, we don’t talk much. We draw pictures together. And that’s always a lot of fun.

What are you reading now?

I always read several books at once. The titles depend on what I am writing at the moment or what I’m planning to write in the near future. For the last year and a half, while I was writing The Haunting of Falcon House (will be released next year by Macmillan), I read Russian classics, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Gogol, and Chekov, as well as collections of classic ghost stories. Today, the following books are open around my house and my studio: Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America by Haynes, Klehr, and Vassiliev; Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations by Trahair and Miller; The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB by Andrew and Mitrokhin; Red Scare, Memories of the American Inquisition by Fariello; Witness by Chambers; Thwarting Enemies at Home and Abroad: How to Be a Counterintelligence Officer by Johnson; and last, the most amazing little brochure I recently found: A Program For Anti-Communist Action by Chamber of Commerce in Washington, D.C. 1948.

Yelchin will sit on a panel entitled “A Collaboration of Authors and Teachers: Diverse Perspectives Through Literature” on Saturday, July 18, at the ILA 2015 Conference in St. Louis, MO, July 18–20. This session will address the resounding need for culturally inclusive literature from two angles: writing and publishing diverse books and helping young readers access and engage with those books. Visit the ILA 2015 Conference website for more information or to register.

April Hall is editor of Literacy Daily. A journalist for about 20 years, she has written and edited for newspapers, websites, and magazines. She covered a great deal of educational issues including the roll-out of both Race to the Top and Common Core State Standards.