In a previous post for ILA’s TILE-SIG series, author Carolyn Fortuna discusses how digital literacy is different from other literacies in that, among other things, it’s best acquired through hands-on learning. One potentially promising hands-on application I am exploring with my research team in kindergarten classrooms is the YouTube Kids app.

Since its launch in 2015, the YouTube Kids app has generated a flurry of support and critique. Most concerns have stemmed from inappropriate videos finding their way past the algorithmic filters, such as sadistic Peppa Pig videos or other so-called “YouTube Poop” videos (see Burgess’ in-depth analysis). In response to this criticism, in 2018, YouTube Kids developers created new filters to allow for more parental control. Parents can now create individual profiles for each child, choose the videos they want their children to watch, and turn off searching for younger children or open the search to revamped, “safer” algorithms.

But, when it comes down to it, what does the YouTube Kids app allow for in terms of entertainment and learning for children? In this post, I describe some of the app's features and how it can be used to enhance digital and media literacy skills.

Features of the YouTube Kids interface

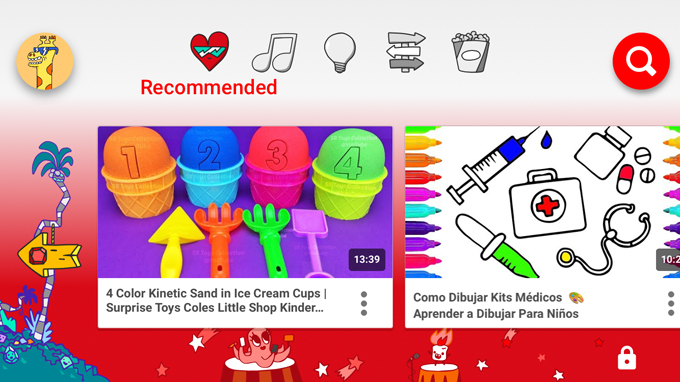

After opening the app, a child must decipher several multimodal images and tools: the supportive images of category icons, the decorative images on the side of each video, and the thumbnails of actual videos that the child can select to watch. Children choose recommended videos by clicking on the thumbnails and swiping for more options.

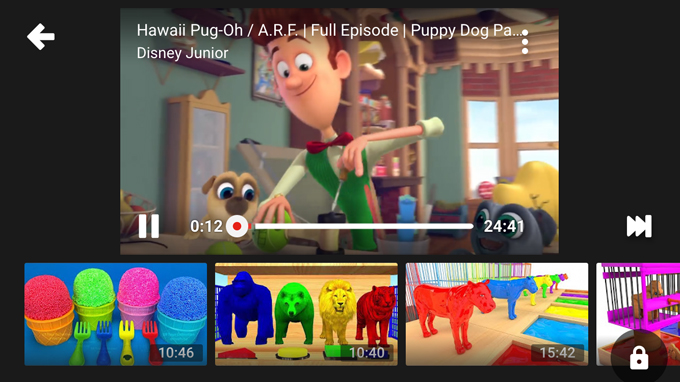

Once the video opens, the child gains access to more controls that overlay the video, including a back arrow, a pause button, a scrollbar to fast forward or rewind the video, and a next button.

Once the video opens, the child gains access to more controls that overlay the video, including a back arrow, a pause button, a scrollbar to fast forward or rewind the video, and a next button.

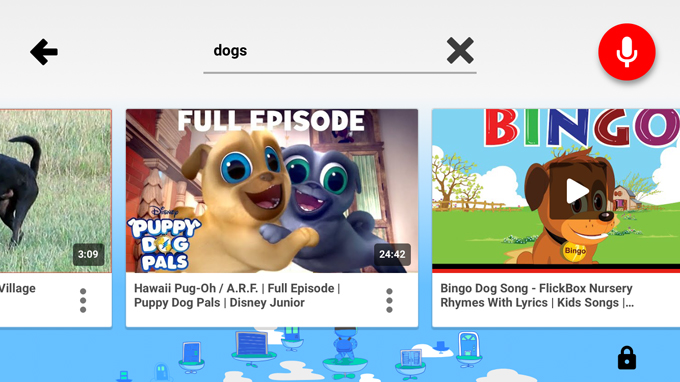

Another multimodal feature is the search function, which provides opportunities for children to practice media literacy skills. Children can use the search feature to explore a topic (such as “dogs” in the image below). Children can learn to search by using the microphone or search bar. Then, a selection of recommended videos appear in the same format as the home screen. The familiar elements across different parts of the interface helps build confidence as children begin to intuitively interact with newer parts of the app to navigate the space more independently.

Challenges become opportunities to teach media literacy

As with most digital tools for young children, the interface is not without its challenges, especially when children use the app on their own. Although the selection of recommended videos shown with each video creates choices for the child, the interface also enables and encourages children to seamlessly watch more videos. While parents and teachers can set a timer within the app, it isbetter for children to learn how to set limits for their own consumption.

Narrowing down search terms to recognizable words for the computer algorithm can sometimes be difficult for children to understand. Moreover, as Google warns, unless a parent has turned off searches, searching in YouTube Kids is governed by algorithms, rather than by humans. The search feature is more open, therefore children will need more skills to navigate that feature on their own.

Before allowing our children to use this app on their own, fostering media literacy is imperative. Parents and teachers should set aside time to prepare children to interact with the app (e.g., helping them to set their own boundaries for video consumption, along with practicing other media literacy skills, such recognizing semiotic cues in the thumbnails of recommended videos or in searches to suss out inappropriate content on their own). Media literacy at home and at school could make the difference between a child who consumes YouTube media with awareness and one who is reliant on the YouTube Kids’ interface and its inherent faulty algorithms that are beyond their control.

Damiana Pyles is an associate professor at Appalachian State University. After teaching as a lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Wyoming, she decided to pursue her PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where her research interests focused on media production, identity, and media literacy practices in order to understand the intersections of the visual, the spoken, the written, and the performed in digital and print literacies in youth media production in non-profits across the U.S. Her current research projects include exploring literacy and science learning in kindergarten classrooms, understanding parent and teacher beliefs about preschool literacies, and exploring concepts of space and place around Instagram and local organic farming.