To paraphrase Aristotle, excellence is habit-forming. The winners of this year’s Coretta Scott King Awards for Author and Illustrator—Rita Williams-Garcia and Bryan Collier, respectively—are exemplars of artistic excellence.

To paraphrase Aristotle, excellence is habit-forming. The winners of this year’s Coretta Scott King Awards for Author and Illustrator—Rita Williams-Garcia and Bryan Collier, respectively—are exemplars of artistic excellence.

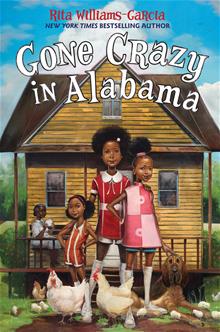

Each title in Williams-Garcia’s trilogy about the Gaither sisters has won the Coretta Scott King Author Award—One Crazy Summer (Amistad, 2011), P.S. Be Eleven (Amistad, 2014), and the 2016 winner—Gone Crazy in Alabama (Amistad).

Just as impressive are Bryan Collier’s Coretta Scott King Illustrator Awards, which have coincidentally mirrored the winning years of Williams-Garcia—Dave the Potter (Little, Brown, 2011), Knock, Knock: My Dad’s Dream for Me (Little, Brown, 2014) and Trombone Shorty (Abrams, 2016).

These awards come as the result of hard work, determination, and talent. To see why these two talented artists are so often honored, one only has read about their approaches to their craft.

Deborah Thompson: Have you always wanted to be an author?

Rita Williams-Garcia: I’ve been scribbling stories since kindergarten….By the seventh grade, I was writing 500 words a night for my novel about my elementary grade school adventures….I was also a reader, and I strongly urge young writers to read even more than they write. Reading puts the sound of the page in your ear. You become that much more intuitive when language resides deeply inside of you. You also learn to infer, deduce, and anticipate. Your critical awareness becomes heightened, and those skills will come in handy as you work through issues in plotting and scene development.

DT: What did you learn along the way to getting your first manuscript accepted?

RWG: The best thing I did for myself was put together a grammar and style booklet containing my grammatical habits, and include an editorial checklist of items to ask myself during my drafting and pre-submission editing. For example, “Account for time?” which is making sure events occur in a reasonable amount of time. “Sequence?” which is making sure lists are relayed in logical sequence and events happen in logical order. Spatial relationships and time are things I don’t think about when I’m generating writing, but when it’s time to wear my reviewing or editing cap—which is much later in the process—I take a closer look at those issues.

DT: Visit almost any elementary classroom and one will find a chart with the writing process listed: prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, sharing/publishing. It’s a linear process. What do you think of this process as one who writes for a living?

RWG: First, let me say that what I do and how I developed as a writer happened outside of the classroom. So, I simply wrote! I think if I had to share my work, I wouldn’t be a writer today. It takes quite a while for a scene, character, idea, essay, or story to fully form. The best thing about writing is knowing you can rewrite it or scrap it. That said, every developing writer can benefit from constructive feedback.

DT: What advice would you give teachers about teaching writing?

RWG: It takes a while for words to become more than just that. Writing comes in stages. It’s more important for the writer to simply be active in the process. To write. To move things around. To think and rethink. To scribble without fear that it’s wrong.

DT: In a 2014 New York Times article, the late Walter Dean Myers lamented the dearth of children’s and YA titles written by African American authors. His argument was almost the same that Nancy Larrick made in 1965. Why do you think that in 50 years, very little has changed?

RWG: This is such a complex question, but also a simple one. The culture must change how we view books of diversity. In spite of how books are positioned or marketed, at every possible level, we must start to see books as books, and then invite more types of books to the party. I primarily write from an African-American perspective, be it urban, suburban, contemporary, historic, etc. I don’t mind getting a spike in my book sales during Black History Month, but these books and all others make great reading all year around. They are open to everybody. If you’re outside of the social, cultural, historical experience, then these books are an invitation to step inside.

DT: What can be done about the lack of diversity?

RWG: Everyone has a role to play in the quest for diversity. Writers write, publishers publish, schools and libraries buy more books with diverse characters that cover different genres, subjects, tones, etc. Shake it up a little by also selecting books outside of the same subjects associated with a particular group. I’m thinking about Teresa E. Harris, whose The Perfect Place (Clarion) incorporates mystery in her middle grade novel, and Kekla Magoon, whose Shadows of Sherwood (Bloomsbury) offers a fresh look at the Robin Hood mythology. Treat your mind to something new! Everyone should invite themselves in by picking up a book they wouldn’t ordinarily read.

***

Deborah Thompson: How did you become interested in illustrating books for children?

Bryan Collier: Right after I graduated from Pratt (Institute in Brooklyn), I walked into a Barnes & Noble and noticed there were no books that reflected people who looked like me. I set about searching for books with faces that looked like mine. It is this search that was my entrée into children’s book illustrating.

DT: How do you begin a piece?

BC: When I receive a story, I read it several times all the while creating a visual mapping of the text. I then enlist different family members as models. I pose them in action and take photos, and from the photos create the illustrations. For example, my nephew, who is now in his 20s, was the model for the boy in Uptown (Henry Holt).

DT: How, if at all, has your art technique changed since the publication of Uptown?

BC: I still use watercolor and collage—but my approach has changed. It’s how I see colors; colors have become symbolic. Take note of the illustrations, the colors. Yellow, for example, is a character in Rosa (Square Fish). Yellow plays an integral role throughout the book. Yellow is the color of the heat of the South, the sun, its glare.

DT: What led you to use mixed media for your illustrations?

BC: The women in my family made quilts, so I grew up seeing patterns. The construction of quilts is akin to the construction of collages. I do sometimes work with oil on canvas and sometimes only watercolor—but mainly collage and watercolor.

DT: How different is it to work with a subject who is still alive such as Trombone Shorty versus illustrating a book in which the subject has passed, for example Martin Luther King Jr. or John Lennon?

BC: In working with a live subject, I am able to talk to that person, pick up nuances. The illustrations happen around the main story—around the edges. I went to New Orleans to meet and talk to Trombone Shorty. He took me around. I got immersed in his world. When I worked on the book about Dr. King, I had breakfast with Mrs. King. I started to get a glimpse of how he was in real life.

DT: Many people are surprised that authors may have no voice or choice in who will illustrate his/her book. How are you chosen to illustrate an author’s work?

BC: A manuscript may have been completed a year in advance before an illustrator is assigned to illustrate it. Sometimes an editor will call my agent, or when an author has a contract, he or she will often ask for a particular artist (e.g., Nikki Giovanni asked to work with me on Rosa).

DT: When I teach art of the picture book, I have my students compare the works of children’s book illustrators with works of classical masters, for example E.B. Lewis with Winslow Homer or Chris Van Allsburg with Edward Hopper. Some of your collage work reminds me of the works of Georges Braque, but whose art would you suggest?

BC: I would say Romare Bearden, and to some extent Braque. Romare Bearden and I took the same journey—from the south to the north. He from North Carolina to Harlem; I from Maryland to Harlem. Romare Bearden’s art was influenced by jazz. He loved jazz and often had jazz playing in his studio. There are jazz overtones to my illustrations as well. In the book Clemente! (Perdomo), I did give an intentional nod to Edward Hopper—the illustration with the ocean in the shadows.

DT: If you had not become a children’s book illustrator, what would you have become?

BC: A chef. Making art is like cooking. My work is an infusion of jazz, gospel, and rock. Making a collage is like making a gumbo.

Deborah Thompson, an ILA member since 1984, is an associate professor in the School of Education at The College of New Jersey. She teaches courses in emergent literacy and elementary reading methods, multicultural children’s literature, and gender in children’s literature.

Deborah Thompson, an ILA member since 1984, is an associate professor in the School of Education at The College of New Jersey. She teaches courses in emergent literacy and elementary reading methods, multicultural children’s literature, and gender in children’s literature.