Spelling is the red-headed stepchild of literacy instruction, derided as crazy and declared unimportant. Spelling lists are created with random unrelated words and taught via rote memorization techniques. Spelling is taught out of context and isolated from grammar, a disastrous combination for students with dyslexia and troublesome for many students without dyslexia. Of course, many students will learn to spell without a hitch, but does that make these practices OK?

Spelling is the red-headed stepchild of literacy instruction, derided as crazy and declared unimportant. Spelling lists are created with random unrelated words and taught via rote memorization techniques. Spelling is taught out of context and isolated from grammar, a disastrous combination for students with dyslexia and troublesome for many students without dyslexia. Of course, many students will learn to spell without a hitch, but does that make these practices OK?

Swap the letter wall for a phoneme wall

Almost every elementary school classroom has the alphabet on the wall. On each letter card is usually a picture of something that begins with the letter on the card. For example, the <a> is almost always accompanied by a picture of an apple, which is trying to convey that “<a> says /a/ like in apple.” The problem is that /a/ is just one of many sounds that the grapheme <a> represents, so we are setting up students for confusion when they come to a word like awake.

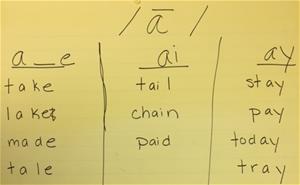

The solution is to hang a phoneme wall, like the one that accompanies this post.

The beauty of this solution is that students can add words as they come up over the entire course of the year and they start to look for and notice sound options for graphemes.

Add a small, but important, qualifying word

In the letter wall example, I included the sentence “<a> says /a/ like in apple,” but that sentence is misleading. We can add one simple word to that sentence to help children understand our spelling system better. Which word could have that much power? The word can. The sentence would then change to, “<a> can say /a/ like in apple.”

Teach the story of the word

Remove the sentences “English is crazy” or “You just have to memorize these words” from your dialogue of teaching instruction. Instead, teach students there is a reason for every letter in every word and investigate that reason together. For example, instead of telling students that it is crazy to have an <l> in the word yolk, look at the story of the word and you will find out that the <l> is there to mark its connection to the color yellow, because yolk is yellow. So do you think students will remember the spelling because they understand the reason behind it or because they were told to memorize it? One great resource to help with sight words is Making Sense of Words That Don’t.

Make spelling lists of related words

The bane of my existence is when I see a list of spelling words that looks something like this:

high, every, hear, west, checked, grand, value, area, dress

This list has words with different spelling conventions, different grammatical features, and apparently no relation. It makes no sense. What about a spelling list like this one?

action, acting, activate, activation, reactivation, value, valuation, valued, invaluable

On the surface, it looks like students are learning only two words, but in actuality (which is another word we could add to this list), students are learning the underlying structure of words. They are learning that every word has a base and an affix or affixes and that those affixes are connected to grammar. Students learn that action is act + ion, and reactivation is re + act + ive + ate + ion. They learn that the single silent <e> in the suffix <ate> is elided because of the vowel suffix that follows it. They learn that <ing> is an inflectional suffix that can make <act> a noun and an adjective and that the <ive> + <ate> can make the word a verb. How cool is that? With this information, students are able to find those patterns in thousands of other words.

Think about this for a minute: If you can spell a word you can read it, but being able to read a word does not guarantee you can spell it. That sentence could have profound implications for how we introduce literacy skills to our youngest children. Should we teach spelling (orthography) before reading?

Kelli Sandman-Hurley is the co-owner of the Dyslexia Training Institute. She received her doctorate in literacy with a specialization in reading and dyslexia from San Diego State University and the University of San Diego. She is a trained special education advocate assisting parents and children through the Individual Education Plan (IEP) and 504 Plan process. Kelli is an adjunct professor of reading, literacy coordinator, and a tutor trainer. Kelli is trained by a fellow of the Orton-Gillingham Academy and in the Lindamood-Bell, RAVE-O, and Wilson Reading Programs. Kelli is the past president of the San Diego Branch of the International Dyslexia Association, as well as a board member of the Southern California Library Literacy Network. She co-created and produced “Dyslexia for a Day: A Simulation of Dyslexia,” is a frequent speaker at conferences, and is currently writing “Dyslexia: Decoding the System.”

Kelli Sandman-Hurley is the co-owner of the Dyslexia Training Institute. She received her doctorate in literacy with a specialization in reading and dyslexia from San Diego State University and the University of San Diego. She is a trained special education advocate assisting parents and children through the Individual Education Plan (IEP) and 504 Plan process. Kelli is an adjunct professor of reading, literacy coordinator, and a tutor trainer. Kelli is trained by a fellow of the Orton-Gillingham Academy and in the Lindamood-Bell, RAVE-O, and Wilson Reading Programs. Kelli is the past president of the San Diego Branch of the International Dyslexia Association, as well as a board member of the Southern California Library Literacy Network. She co-created and produced “Dyslexia for a Day: A Simulation of Dyslexia,” is a frequent speaker at conferences, and is currently writing “Dyslexia: Decoding the System.”