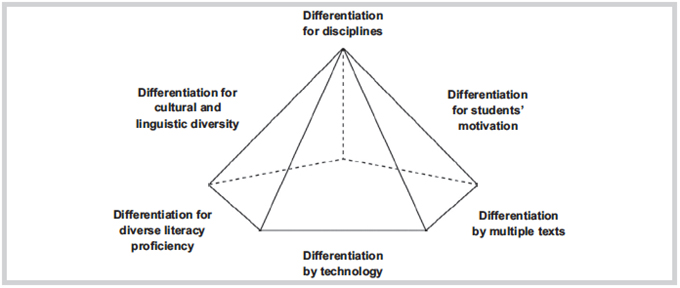

It goes without saying that literacy (i.e., reading, listening, writing, and speaking) is the core set of skills necessary for learning fundamental subjects in the 21st century. Given its importance in learning, educators have coined terms such as content literacy, content area literacy, and disciplinary literacy to better support students’ learning in and across disciplines. More recently, Bong Gee Jang, Dawnelle Henretty, and Heather Waymouth suggested using the term “literacy across the disciplines” in order to encompass “both general and discipline-specific literacy practices within and across academic domains.” In the article, they also emphasized the need for differentiated literacy instruction across the disciplines and proposed a pentagonal pyramid model.

Specifically, this model incorporates three for factors representing student characteristics for differentiation (i.e., literacy levels, cultural and linguistic diversity, and motivation) and two by factors that can be used as tools of differentiation (i.e., technology and multiple texts). In this post, we will introduce an example of integrating technology and multiple texts for differentiated literacy instruction in the science class of a middle school teacher, Ms. Smith.

Ms. Smith’s science unit about air pollution

Ms. Smith is planning to teach a unit on air pollution to eighth-grade students. Having recently read articles about air pollution coming from local factories and wildfires in Los Angeles, she decides to center her pollution unit on a question relevant to her students’ lives: “What are the issues about local air pollution and what should be done to improve local air quality?”

Differentiation for diverse culture, language, and literacy proficiency through multiple texts and technology

In Ms. Smith’s eighth-grade science class, about half of the students are English language learners or have below grade-level proficiency in reading. To ensure all students have adequate prior knowledge about local air pollution, she creates a list of the following resources:

- The Los Angeles Daily News article, “Southern California Still Has Some of the Worst Air Pollution in the Country, Report Finds”

- The Airnow Students website, which provides kid-friendly information about air pollution, current air quality index (AQI), forecasted AQI, current ozone, and more

- The CBS News article, “More Than 20 California Cities Have Unhealthy Air Quality From Wildfires”

- The California Statewide Fire Map

- This Pacific Standard opinion piece, "The Fear of Dying’ Pervades Southern California’s Oil-Polluted Enclaves”

- The South Coast Air Quality Management District’s website, which provides a variety of information about air quality issues in the South Coast areas and their efforts to improve the air quality

To improve students’ understanding of the materials regardless of their language proficiencies, she carefully creates heterogeneous groups and asks them to complete the same tasks after reading different texts, such as the following:

- Group A: resources no. 1 and no. 2

- Group B: resources no. 3 an no. 4

- Group C: resources no. 5 and no. 6

Each group watches and reads the assigned resources and organizes the available information about focal topics (i.e., air pollution status, causes of air pollution, impact of air pollution, current solutions for air pollution, and further actions to be taken) from the resources into tables, concept maps, and/or diagrams using online infographic tools such as Infogram and Venngage. Students who are proficient in languages other than English can also obtain information from resources through help from peers, the 40 different language supports embedded in the websites (resource no. 6), or Google Translate.

Once each group completes the tasks, the students report what they found to other students. As a wrap-up activity, Ms. Smith cocreates a map about the current air quality and causes of air pollution in the Greater Los Angeles area using Google Maps’ Create Map function. Overall, this activity contributes to promoting students’ active engagement with a variety of literacy levels in her class because the use of their local knowledge, culture, and experience is valued and shared in this activity with multiple texts and technology tools.

Differentiation for students’ motivation through technology

As the final product of the inquiry-based project, Ms. Smith provides students with two options. The first is to write a letter/email to a state representative or to the editor of a local newspaper in order to draw his or her attention to this issue and to ask him or her to take action. The other option is to create a video showing and describing the status of air pollution, its direct and indirect impacts on the students and their family and community, and the possible efforts to improve air quality.

After completing the final product, each student will be required to send the letter/email or publish the video on YouTube and share the link via social media (e.g., Instagram and Snapchat) that they have access to actual audiences. By providing options on the genre (i.e., persuasive vs. informative), platform (i.e., print-based vs. digital), and modality (i.e., monomodal vs. multimodal), students can make choices based on their abilities and preferences, and the realization that they are capable of doing the work can motivate them. Letting students have real and authentic audiences is another way of motivating them because it allows them to receive feedback and reactions from real people.

We hope this example from Ms. Smith’s class helps educators better understand the pentagonal pyramid model of differentiated literacy instruction across the disciplines and gives them ideas for its application in their teaching.

Sohee Park recently finished her doctoral study in education at the University of Delaware. She is currently participating in several research projects on digital/multimodal literacies, writing instruction, and struggling readers.

Bong Gee Jang is an assistant professor in the Department of Reading and Language Arts at Syracuse University. His main areas of research include literacy motivation and engagement in digital settings and disciplinary/content literacy. His research has appeared in referred journals such as Reading Research Quarterly, Educational Psychology Review, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, and The Reading Teacher. Jang teaches courses related to disciplinary literacy and language arts for both preservice and inservice teachers. He also teaches introductory and advanced quantitative method courses to graduate students.

This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).